The Future of Network Fabrics

Turning Fabrics Inside Out

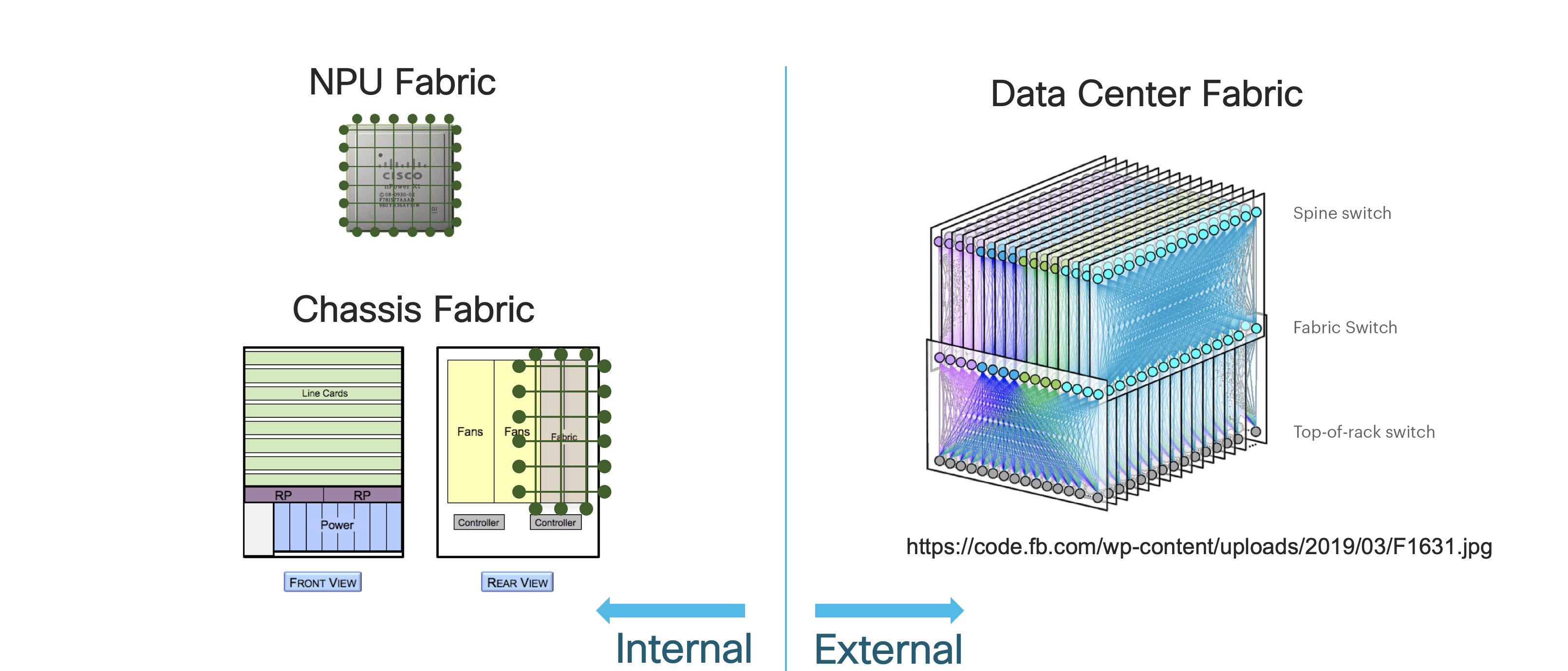

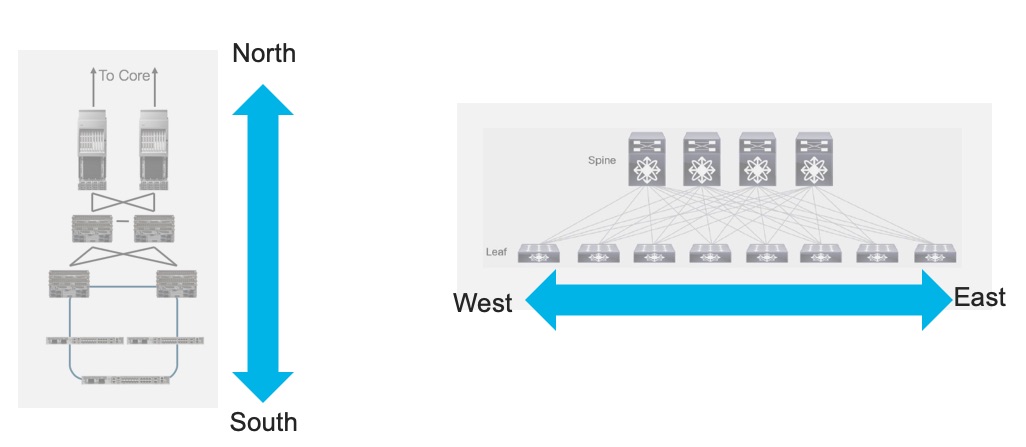

Until recently, the notion of a “fabric” in a network was confined to single device: the switching fabric inside an NPU or ASIC, the fabric module of a modular router, or the fabric chassis of a multi-chassis system. All these internal fabrics fulfilled the same basic function: non-blocking connectivity between the input and output ports of the system.

Largely driven by the needs of the massively scalable data center, a new network design has quite literally turned fabrics inside out. Instead of building fabrics inside silicon, data center fabrics provide (statistically) non-blocking connectivity by connecting simple devices in a densely connected spine and leaf topology. These designs can be relatively small (e.g. replacing a large modular device with a fabric of small devices) or as massive as the data centers they enable (e.g. Facebook’s Data Center Fabric).

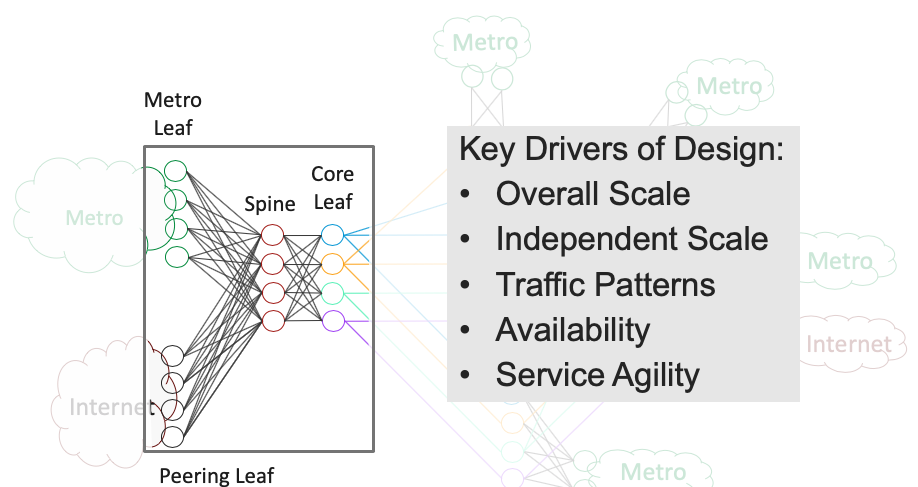

As every network architect knows, there is no one “best” design for a network. Every design represents tradeoffs. Large scale fabrics have been very successful in the data center. The question is: are fabrics sensible in other parts of the network as well? Let’s look at that from a couple of angles: scale, availability, traffic patterns, and cost.

Scale: Up and Out

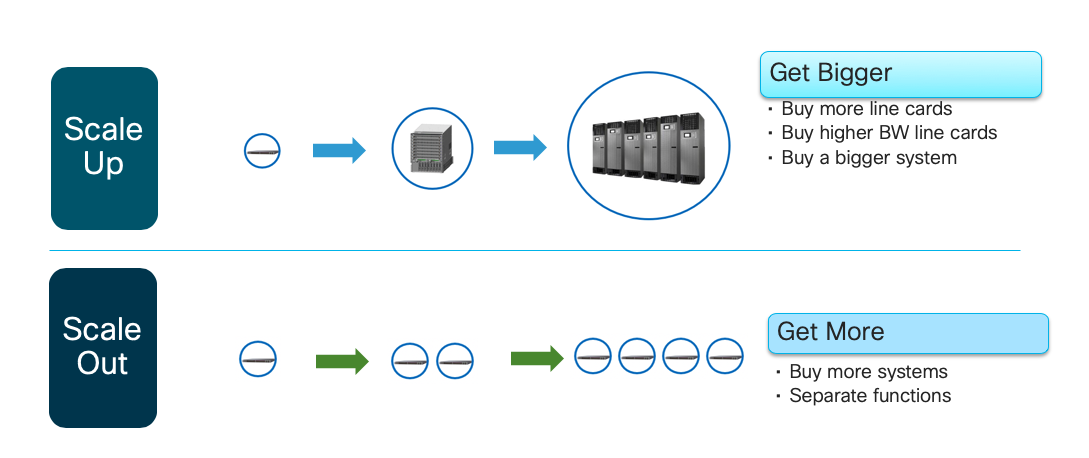

When designing networks, scale is almost always top of mind. There are two basic paradigms for scale: scale out and scale up. Networking has traditionally relied primarily on a scale up paradigm: when you need to scale, buy a bigger box or more line cards or denser line cards. Scale out, used almost exclusively in cloud-scale computing, takes the opposite approach. Instead of buying bigger boxes, buy lots of smaller ones.

Scale out can scale very large. The Cisco NCS 5516, a large 100GE routing platform, today provides 576 100GE ports. An external fabric built entirely of 48-port NCS 5502s could support up to twice that many ports. If you put NCS 5508s in the spine, you could get up to 6912 user-facing ports. That’s truly massive scale.

Scale Impacts Availability Impacts Upgradability Impacts The Bottom Line

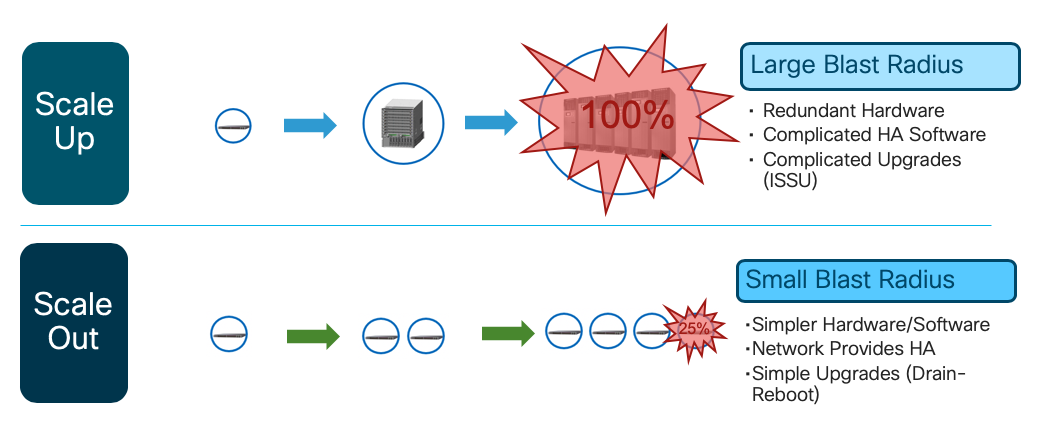

How you scale has a direct impact on how you achieve high availability in a given design. When you scale up, those ever-larger and denser devices create an ever-larger “blast radius.” If you could lose a big chunk of your network capacity when a single device goes down, you’ll want to harden that device with lots of redundant hardware and complex software to keep it all running. Unfortunately, complex, tightly coupled systems like this can be difficult to upgrade and troubleshoot. If you can’t upgrade quickly, you might delay critical bug fixes as well as new features that could enable profitable new services.

When you scale out, the blast radius of an individual device is smaller. Without the complexities of large, redundant systems, networks made out of many small, simple devices can achieve very high availability. The smaller the blast radius of a device, the easier it is to take it out of service for upgrade. Since upgradability has a direct impact on both quality and service agility, a scale out network should be able to deliver higher quality services, faster.

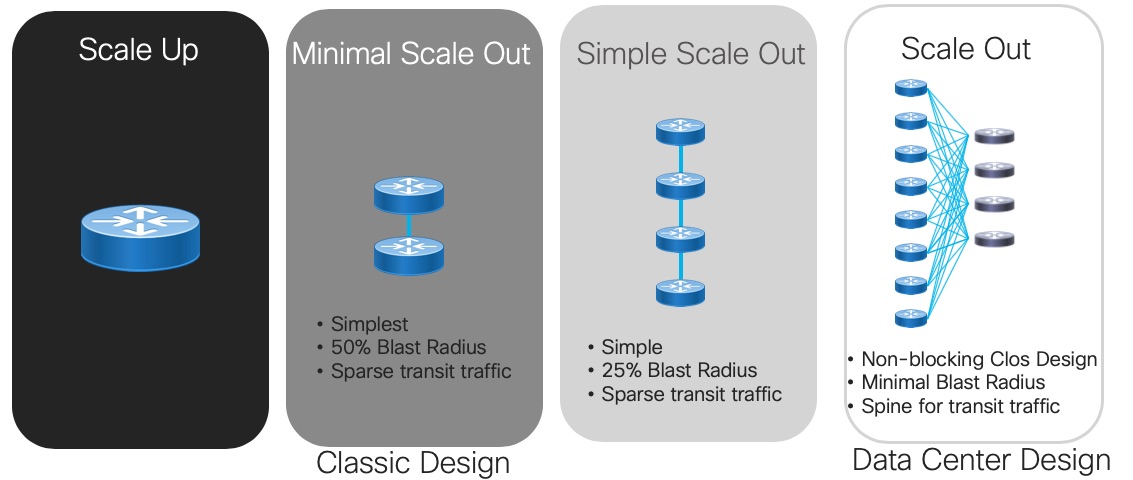

Traditionally, networking has had a bias for scale up, but in truth scale out and scale up exist on a continuum. Even in traditional designs, two routers are usually deployed in a given role for redundancy. Two is the smallest amount of “scale out” possible, but it’s still “scale out.” Of course, the ultimate in “scale out” is the full spine and leaf fabric design of data center fame, but there are designs that balance “scale out” and “scale up” to achieve the right fit for purpose.

Traffic Patterns: Is An East-West Wind Blowing Your Way?

Massive data center fabrics arose out of the need to provide equidistant, non-blocking bandwidth for traffic between storage and compute components distributed across the data center. This is what is called an “east-west” traffic pattern, in contrast to the “north-south” pattern that characterizes classic Campus and Service Provider designs. When north-south traffic predominates, one or two large chassis can provide the requisite aggregation function very efficiently.

Having a clear understanding of the traffic pattern you need to support is crucial in understanding if fabrics are right for you. There are certainly places in the network where traffic patterns are changing very rapidly today. For example, the rise of local peering and caching in Service Provider networks means that traffic that might once have been aggregated and sent across the backbone can now be served locally instead. That introduces a strong east-west component into what was once an almost entirely north-south pattern. Introducing a fabric with a spine layer to provide connectivity between PE nodes and Peering or Caching nodes starts to make sense in that scenario.

Having a spine allows you to attach diverse leaf devices, some “heavy” (richly featured, more expensive) and some “light” (basic features, less expensive). You can also scale each leaf type independently. If your peering traffic is growing faster than core-bound traffic, just add more peering leaves. When you want to introduce new features, simply plug a new-feature-capable-leaf into the spine and away you go. If it doesn’t work the way you want, unplug it. There’s no impact on other services, no downtime for upgrades.

Good Fabrics Are Not Free

Some people assume that fabrics will be less expensive than modular systems because fabrics are built from smaller, simpler, cheaper devices. This overlooks a couple of important points. First, it takes a lot of spines and leaves to achieve a statistically non-blocking architecture. For example, to build a non-blocking 96-port fabric out of 48-port devices, you need…wait for it…six 48-port devices (2 spines and 4 leaves). Now we’ve gotten very good at building cost-effective NPUs for routers, but you still need to connect all those spines and leaves. The optics required for all that connectivity quickly comes to dominate the cost of an external fabric. Using Active Optical Cables (AOCs) can help mitigate the optics cost but it remains non-negligible.

Speaking of connectivity, remember that connecting spines and leaves will take a lot of cables. For our example of 96 user-facing ports, you’ll need 96 cables between the spines and leaves for fabric connectivity. That effectively doubles the number of cables your ops team has to manage.

In terms of space, power and cooling, fabrics exact a cost as well. We build large, modular systems for a reason: they are very efficient. In apples-to-apples comparisons (e.g. same ASIC family), a fabric of small devices always consumes more space and power for the equivalent number of ports in a large chassis.

The larger number of devices and interfaces in a fabric will naturally have an impact on your control plane. Take our simple example of the 96-port fabric. Can your IGP scale 6X for those additional devices? Depending on the size of your network, that may be entirely reasonable, since IGPs today can easily handle thousands of nodes. For very large networks, however, this could be a significant concern.

Given the ratio of capex to opex (typically 4:1 for Service Providers), it’s also important to take a good hard look at the impact fabrics can have on the ops team more generally. In our 96-port example, ops has to manage six devices (six management address, six ACL and QoS domains, six IGP instances, etc.) where before they might have had only one. We know from massive data center designs that the only way to scale ops like that is to go all-in on automation. From cable plans to config generation and deployment to upgrade to troubleshooting, every aspect of network operations will have to be automated.

Conclusion: To Fabric or Not To Fabric?

Thanks to the work done in data centers large and small, we know the costs and benefits of network fabrics. For sheer scale, availability, upgradability, and east-west traffic patterns, it’s hard to beat a fabric of small, simple devices. But the large number of devices in external fabrics makes large-scale automation an absolute requirement. Until fabrics go mainsteam, much of that automation will remain bespoke. And don’t expect to optimize cost by deploying a fabric. Port for port, optics, cooling and power all favor a modular system over an equivalent fabric by a significant margin.

So are fabrics fated to stay inside NPUs, chassis and data centers forever? Not necessarily. At some point, the physics of NPUs will reach a point that we can no longer build highly efficient large modular routers. That point might be 10 years in the future, but it is coming. In that sense, fabrics are inevitable. And as William Gibson famously said, “the future is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed.” Even today, some service providers have weighed the cost and benefits of fabric architectures and decided that the availability, scale, upgradability and flexibility of fabrics outweigh the upfront capex and opex investments for the traffic patterns they need to support. Fabric architectures are not evenly distributed, but they are already emerging as a valid design pattern in modern networks.

Finally, many network architects are coming to see that you can realize some of the benefits of fabrics without going to a full-scale spine and leaf design. For example, adding a little more scale out (say 4 or 8 routers in an LSR or LER role instead of the traditional 2) can enable a smaller blast radius and easier upgrades without the massive device scale of a full spine and leaf fabric. This might stretch (sorry) the data center definition of fabrics, but it’s a step closer to the availability, upgradability, quality and service agility that every network needs.

Leave a Comment