Internet Traffic Trends

Introduction

Over the last five years Internet traffic has been driven by one dominant source, unicast Internet video. The rise in Internet video has its roots in how user viewing habits have changed as unicast video delivery became more viable as an alternative to broadcast or multicast delivery. The capacity requirements of modern video delivery require rethinking networks to make the most efficient use of resources at all layers. This two-part blog series will first cover how video delivery has evolved to bring us where we are today. The second part will cover network architecture and technology to help improve network efficiency to deal with the rising tide of unicast video.

Unicast Video Growth

Broadcast Video History

Television video delivery for many years followed the same path blazed by radio before it, broadcasting a single program over the air at a specific time to anyone within range of the signal. Cable networks were built in the 70s and 80s, with the promise of delivering a wider variety of content to subscribers not subject to the same impairments as over the air (OTA) broadcasts, while eliminating the use of antennas. A physical medium like coaxial cable exhibits similar properties as transmission through the air as electrical signals are replicated across branches in the medium. The original primitive cable networks were still analog end to end and built for broadcast delivery of all video to every user. Satellite video delivery worked in much the same way, simply broadcasting all signals and requiring the end device tune to the channel at a specific analog frequency and the user tune in to watch at a specific time of day. In the 1980s and 1990s, TV viewers could always cite the exact day and time of their favorite programs. While broadcast video has limitations on flexibility for users, it has the ultimate efficiency when it comes to network resources as the signal is broadcast once to all users once at the origin.

Video on Demand

Video on Demand, or VoD, originated in the late 1980s and rose to prominence in the 1990s as a way to deliver video content to users on their time, not tied to a broadcast schedule. Viewers could now select what they wanted to view and have it be delivered to them immediately. It took the reduction in cost of the base infrastructure components, mainly storage and compute, to make a service like VoD a reality. VoD was also seen as a way to further monetize the cable network and challenge the huge video rental business that existed during those times with Pay Per View (PPV) content.

VoD delivery used two different methods for delivery back in its original form, push or pull. In the push method, content was delivered via broadcast to a single or all subscribers and stored locally on a device such as a set-top box, for viewing later. The pull method streamed the content to the subscriber device from a remote server on user demand. In the end, the pull method easily won out due to the much larger variety of content available and less costly end user device. In order to support a single user viewing content destined for only their device, it required dedicating analog spectrum for the channel. It was still broadcast to a number of users, but encrypted such that only the paying subscriber could view it. Even though it was still analog broadcast at the lowest level, the content was unicast to a specific subscriber by consuming resources for a single video stream destined to a single viewer. VoD fundamentally changed users viewing habits and also introduced the first unicast video delivery.

Video over IP

Service providers who built out wireline networks using DSL and Ethernet technology, network infrastructure types not having a native analog video delivery method, looked at IP as the higher layer protocol to deliver video content to users. These networks were deployed to take advantage of multicast, a subset of the broadcast capability inherent in Ethernet, and standardized for IP in RFC 1112. IP multicast improves network efficiency by implementing frame replication in the network devices, combined with a set of control-plane protocols to create optimized distribution trees. In its simplest form IP multicast replicates a broadcast network, sending all channels to all users (dense mode), and some providers used this method. However, to improve network efficiency it is now most common for end devices to use protocols like IGMP (v4) and MLD (v6) so optimized multicast trees are built. This type of multicast IP delivery is known as IPTV and is implemented in North America by networks such as AT&T UVerse and Google Fiber.

}

}

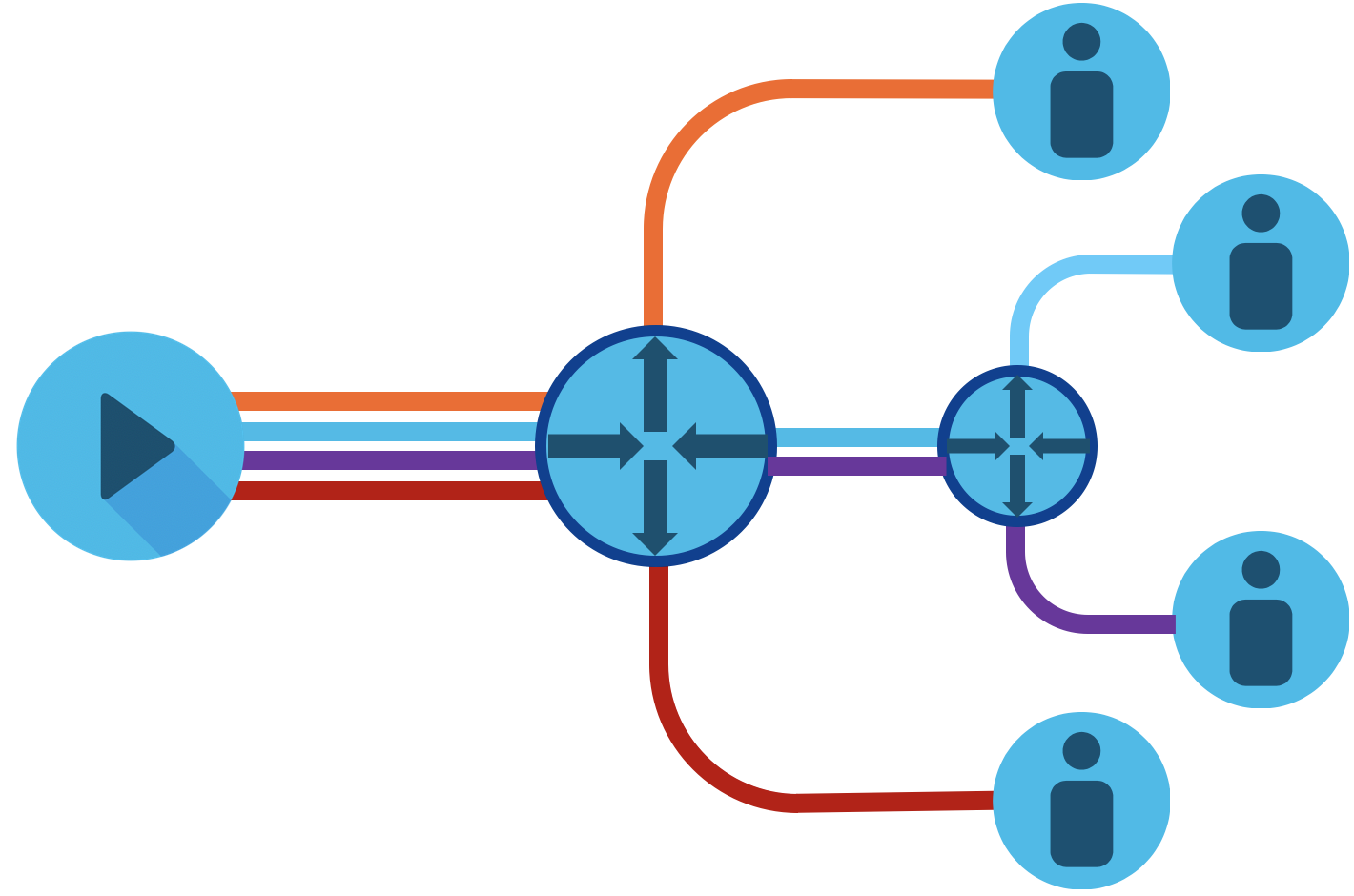

Supporting VoD on these networks requires delivering video over IP. Similar mechanisms can be used as analog networks, using a specific multicast address for the subscriber stream. However, instead of simulating a unicast stream using a more complex multicast process, streaming the content as a to a unicast IP address assigned to a device is much simpler and supported a wider range of devices, even across networks that do not support native multicast delivery. Today more and more content on wireline networks is delivered using unicast IP, even on traditional cable networks, due to its flexibility and the ability to serve content to a variety of end user devices from a single content source. The flexibility and ease of delivery using unicast IP has superceded the inefficiencies of delivering duplicate content over the same network resources.

}

}

Over the Top IP Video

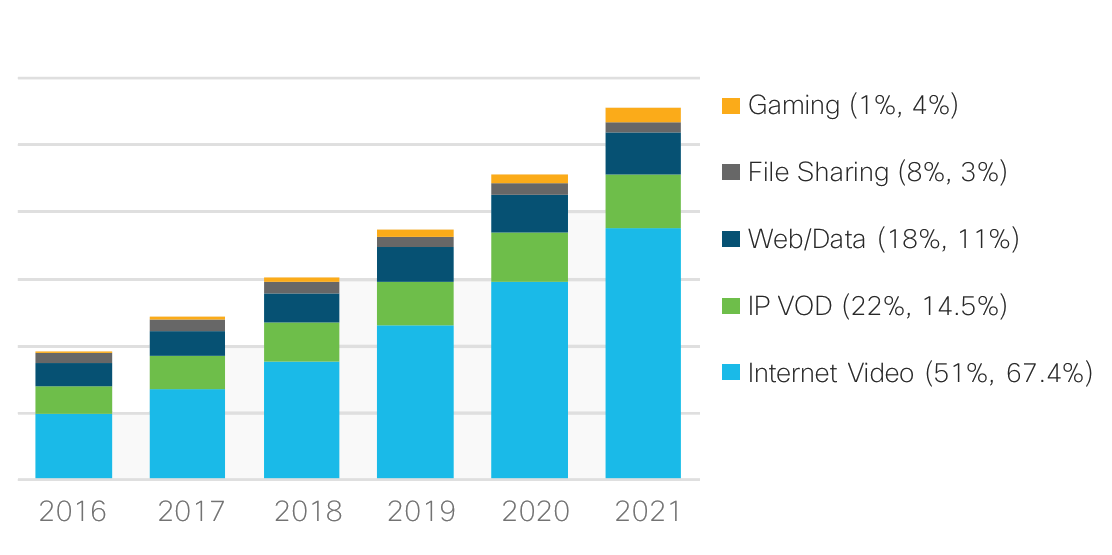

The unicast video content described above has typically been contained within a service provider network. As the Internet has grown and bandwidth to end users increased, video content from alternative sources emerged. Broadband Internet became more widely available in the mid 2000s and with it came user-generated video providers like YouTube along with traditional media rental companies like Netflix embracing streaming video for rental delivery. These Internet content providers deliver video “over the top” (OTT) of service provider networks since the origin and destination are applications controlled by the content provider. The growth of OTT Internet video has continued to climb rapidly over the last decade along with IP video in general. IP video accounted for 73% of all Internet traffic in 2016, and by 2021 will account for 82% of all Internet traffic. The most rapid increase is in over the top Internet video, shown in the graph below from the Cisco VNI.

It is not only on-demand content driving OTT growth, streaming of traditional broadcast video like sports to mobile devices, tablets, smart TVs, and additional endpoints is increasing in popularity. The last few years have seen a number of new services delivering traditional linear (live) TV using OTT IP delivery. Over the top video is by nature unicast, as each stream is simply sent on demand when a user clicks “play.” Since there is little efficiency in sending a single stream to each user, it causes tremendous strain on network resources. It is however a trend that is unlikely to change, so new methods need to be employed to improve network efficiency and build networks to handle increasing video traffic demands.

Producers and Consumers

Content Providers

Content providers are those who originate video streams. A content source could also be a service provider providing video content to its own subscriber base, or an OTT Internet video source. A content provider may not be the original origin of the content, but is simply a means to deliver the content to the end user. d

Caching and Content Delivery Networks

Caching is the process of storing content locally to serve to users instead of utilizing network resources to retrieve the content each time the content is accessed. Caching of Internet content became popular with the rise of the Internet in the late 1990s with open-source software such as Squid and commercial products like Cacheflow and Cisco WAAS. Called “transparent” caches, they intercept content without the source or destination having knowledge of the caching. The content in those days was mainly primitive static content, but with the high cost of bandwidth, it was still sometimes beneficial to cache content. Transparent caches have evolved into systems today targeted at OTT providers, and use more sophisticated techniques to cache video content from any source. However, with the rise of end to end encryption use, transparent caches are no longer a realistic option for serving content closer to users.

Content Delivery Networks (CDN) have been around for many years now, with the first major CDN Akamai going live in 1999. The aim of a CDN is to place content closer to end users by distributing caching servers closer to end users. CDNs such as Akamai, Limelight, and Fastly host and deliver a variety of content from their customers. In addition to more generic CDNs, content owners have built their own CDNs to deliver their own content. Examples of dedicated CDNs include the Netflix OpenConnect network and Google Global Cache network. Most new streaming video providers utilize a distributed CDN to deliver content. Each CDN uses proprietary mechanisms for request routing and content delivery, so providers must use analysis to determine which ones are the most optimal for their network.

Eyeball Networks

Wireless and wireline service providers providing the last mile Internet connection to end users are commonly known as “Eyeball” networks, because the all content must pass through those networks for end users to view it. Around the world, and especially in North America, consolidation of service providers have left relatively few Eyeball networks serving a large number of subscribers.

Efficient Unicast Video Delivery

What is Network Efficiency?

Network efficiency in this context refers to minimizing the cost and consumption of network resources such as physical fiber, wavelengths,and IP interfaces to deliver unicast video content to end users. The equation to delivering video traffic efficiently is to create a network model reducing the distance, network hops, and network layer transitions between the content provider and content consumer while maintaining statistical multiplexing through aggregation where beneficial.

Role of Internet Peering

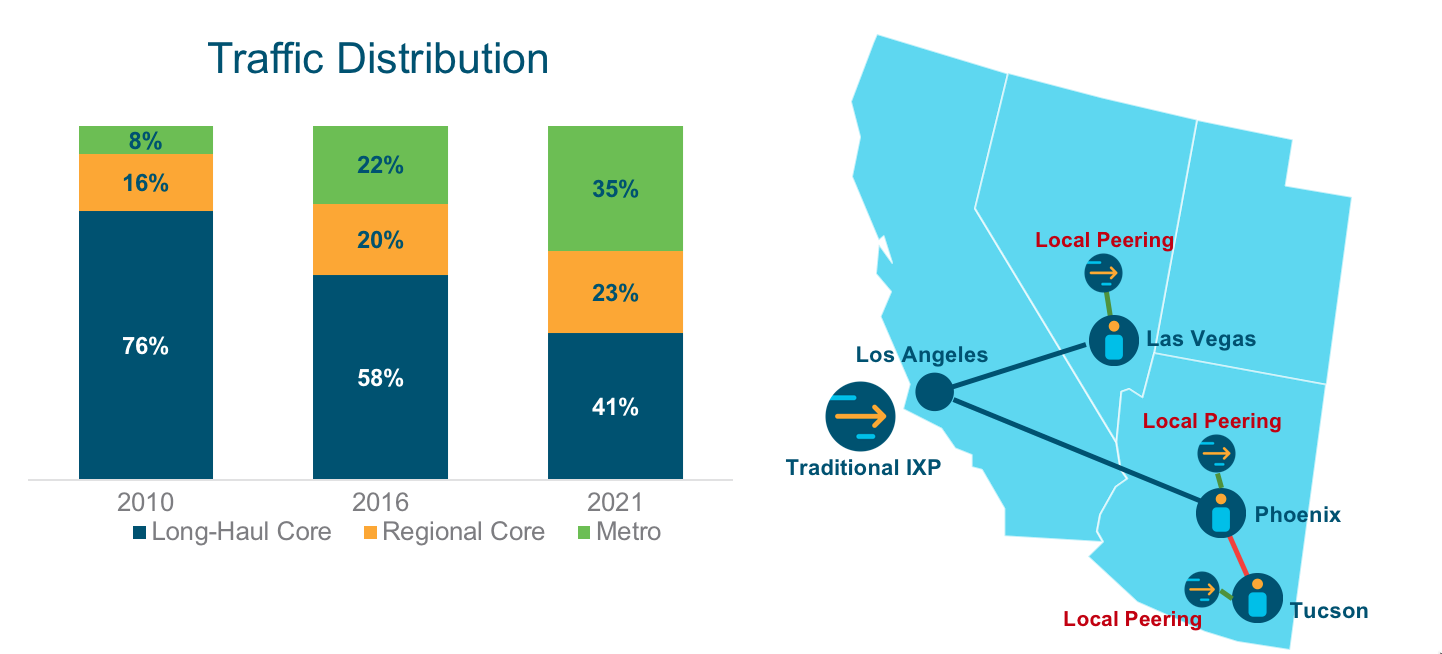

Internet Peering is the exchange of traffic between two providers. Peering originated at third party carrier-neutral facilities known as Internet Exchange Points (IXP), with the exchange providing a public fabric to interconnect service providers. Due to consolidation and the dominant traffic type being video, the Internet has evolved from most content flowing through a Tier-1 Internet provider via transit connections to one of direct traffic exchange between content providers and eyeball networks. The majority of Internet video traffic today is exchanged via private network interconnection (PNI) between content providers and eyeball networks. The concept has been coined the “Flattening of the Internet” as the traditional hierarchical traffic flow between ISPs is eliminated. Traditional large IXPs still act as meet-me points for many providers, facilitating both public and private interconnection, but improving network efficiency demands traffic take shorter paths.

Localized Peering

Reducing the distance and network hops between where unicast video packets enter your network and exit to the consumer is a key priority for service providers in reducing network cost. Each pass through an optical transponder or router interface adds additional cost to the transit path, especially on long-haul paths from traditional large IXPs to subscriber regions. The aforementioned rise in video traffic demands peering move closer to the edges of the network to serve wireline broadband subscribers along with high-bandwidth 5G mobile users. Content providers have invested heavily in their own networks as well as distributed caches serving content from any network location with Internet access. Third party co-location providers have begun building more regional locations supporting PNI between content distributors and the end subscribers on the SP network. This leads to a localized peering option for SPs and content providers, greatly reducing the distance and hops across the network. As more traffic shifts to becoming locally delivered building additional regional or metro peering locations becomes important to ensure less reliance on longer paths during failures.

Service Provider Unicast Delivery Headend

As mentioned, service providers are seeing growth not only in OTT unicast video delivery, but also delivery for their own video services. Most service providers have deployed their own internal CDNs to provide unicast video content to their subscribers and migrate VoD off legacy analog systems onto an all-IP infrastructure. The same efficiency tools for dealing with off-net content from peers applies to on-net video services. There may be efficiencies gained in placing SP content servers in the same facilities as other content peers, aggregating all content traffic in a single location for efficient delivery to end users.

Express Peering Fabrics

See how Express Peering Fabrics can help drive efficiency into service providers networks in the next blog in this series.

Leave a Comment