An Update on Router Buffering

Intro

Buffering requirements for routers have been a much debated and ultimately unresolved topic since the beginning of the Internet. This paper presents a technical foundation for network designers to assess buffering requirements based on applications as well as network and traffic characteristics. It also provides specific recommendations for common scenarios for use in product selection and as a starting point for deployment. This is a long article, so you may prefer PDF version

Executive Summary

Buffers are the shock absorbers in a network, and their operation is critical to its operation. Router buffering design is essentially determining what to do with packets that cannot immediately be forwarded. While that problem statement is quite simple, the answer is one of the most challenging topics in networking.

In some cases, a network’s applications and their behaviors may be well understood; in others, a router may need to support a wide range of applications. The target application may be specific such as an Enterprise VoIP service or broader, such as web traffic carrier over the Internet.

Application requirements can often be defined in terms of bandwidth, tolerance for loss, latency, and packet delay variation (“jitter”). In addition to the end-user-visible application, the application implementation also impacts network requirements. For example, the transport protocol and the size of the host-side buffer influence a video application’s tolerance for packet loss.

The network architecture and a device’s place in it greatly influence the type of router or switch required. For example, it is usually critical to fully utilize expensive long-haul WAN links, data center routers and switches often have the option of adding additional capacity for a relatively low cost as a way to minimize congestion. Round Trip Time is another key variable that may range from tens of microseconds in a data center to multiple seconds on a congested cellular network – over five orders of magnitude. This factor alone may drive an equally large difference in buffer requirements, which is the reason for a similar range of capabilities among the products on the market today which are optimized for those environments. In addition, a router’s place in the network also determines bandwidth, oversubscription, traffic synchronization, the range of link speeds, and link latency. Router architectures and their impact on buffering are also explored. Key factors include centralized vs. distributed architectures, queuing models (e.g., central, VOQ, egress), the number of buffers, and sharing of buffers. This paper explores these areas and the tradeoffs that should be considered both for selecting and configuring routers. It focuses on the traditional SP router roles, but also highlights the unique characteristics of SP and Web data center networks.

The paper doesn’t propose any single answer but attempts to cut through the dogmatic and simplistic extremes which are frequently proposed so that network designers can effectively evaluate routers in the context of their requirements. Recommendations are made as ranges and guidance is provided to adjust within or outside the range.

In general, the recommendations are lower than legacy buffering requirements developed in the 1990s. Based on these factors, the key recommendations are:

- Core router buffering in the range of 5-10 msec

- Edge router buffering in the range of 10-30 msec

- Data Center buffering is highly dependent on architecture and applications. Low RTT, ease of adding bandwidth, and traffic synchronization are critical considerations.

Network Behaviors as Seen by Applications

Applications have a wide range of requirements from the network, and they have preferences for what the network’s behavior should be when it is unable to immediately deliver packets along the “best” path. Starting with the assumption that applications behave optimally when directly connected over a short distance via a media fast enough to carry all traffic they can generate, what then are the differences between this ideal network and a real network?

The most notable differences in a real-world network that affect service quality are packet loss, latency, reordering, corruption/duplication, and packet delay variation. Collectively, these characteristics define the quality of the network for the application. Packet loss can occur for a number of reasons, most notably: congestion (due to link or router capacity); software bugs; filters (e.g., ACL, uRPF, black holes); incorrect routing; and convergence events. This paper will focus on loss from congestion as it is the most relevant to buffering. Note that these behaviors apply to L2 frames, MPLS frames, or IP packets processed by switches and routers. Unless noted, “packets” to refer to all types user data traffic.

The main sources of latency are propagation delay along the links, nominal device latency, and link-congestion buffering (queuing latency). Propagation delay is a function of the speed of light (3.34 usec per km), but evaluating the latency on a link between two points must take into account the actual fiber path and refraction inside the fiber. A reasonable approximation for the refraction impact for conventional fiber is 1.46 (depending on fiber brand and wavelength) which results in a speed of approximately 5 us / km [M2optics]. A common guideline used in buffering calculations is a maximum terrestrial propagation delay of roughly 125 msec resulting in a max non-congested route trip time (RTT) of 250 msec.

Nominal device latency is the time a packet is delayed by a non-congested network device. This includes time to copy the packet into different memories, to perform packet operations, and serialization delay (the time to send bits onto the fiber, which will be less for faster links and smaller packets). In low-RTT networks like Data Centers, serialization delay can be a significant part of the RTT (1.2 us for 10G and 12us for 1G) and is a motivation for 10G-connected servers in some applications even when traffic is only in the 100s of Mbps. Latency due to buffering results from the inability to forward all packets immediately. This is the shock absorber function. It ranges from small delays for a microburst on a 10G link transitioning to a 1G link to large delays measured in seconds when a low-speed interface with large buffers experiences persistent congestion, especially in under-provisioned wireless networks.

The table below illustrates the range of latency introduced from common sources.

| Duration of Latency | Common Sources |

|---|---|

| 100s of nanoseconds | Nominal latency of ultra-low-latency cut-through switches |

| microseconds | 10G serialization delay, nominal latency of single-chip switches |

| 10s of microseconds | Data Center RTT, Modular routers, 1G serialization |

| 1s of milliseconds | Campus or Metro RTT |

| 10s of milliseconds | Cached CDN RTT, intra-country RTT |

| 100s of milliseconds | Inter-continent RTT |

| 1s of seconds | Congested DSL home router or mobile device |

Table 1 - Common Sources of Latency

Packet Delay Variation (PDV) (often called jitter) is the variation in latency of packets, usually due to transient buffering. It takes the form of dispersion (more time between successive packets at receiver than transmitter) or clumping (less time between packets). RFC 3393 provides a good overview of PDV and a proposal for quantifying it. At a high level, it can be measured by timestamping packets and comparing the relative offset between two packets when they were sent vs. when they were received. That value is then combined with additional samples for analysis. Note that “good” or “bad” PDV is highly dependent on the application context. An acceptable PDV for a file transfer may be catastrophic for voice, gaming applications, or live video. Even for applications that aren’t sensitive to PDV, it has an impact to their performance as TCP considers RTT variation when determining how long to wait before concluding that a packet has been lost. PDV of ACKs can also communicate important information about present and future network congestion to the transport protocol.

TCP Review

A significant majority of Internet, Enterprise, and Data Center traffic runs over TCP. TCP is essentially the “application” that most Service Provider networks are designed for, and its behavior must be considered along with the more specific applications such as stock trading, gaming, or business VPNs. This section presents a detailed survey of TCP with a focus on how it interacts with network packet loss, latency, and PDV. Recent developments in TCP are also presented as its evolution has an impact on buffering requirements.

TCP is a transport protocol that takes a stream of data (not packets) from an application and transports it reliably end to end. TCP divides the stream into segments and hands them off to IP for transmission as packets through the network. TCP handles detection and retransmission for any lost segments and doesn’t pass the stream’s data to the application until it can be delivered in order. Packet loss adds latency while the segment is recovered, which can happen quickly in many networks. This means that loss and latency are effectively equivalent from an application’s perspective when using TCP.

Congestion control is the mechanism that TCP uses to determine when to transmit segments. To implement congestion control, TCP first probes the network by increasing the rate of transmission in order to determine the optimal rate as represented by the number of packets “in flight” at any given time. Once it finds this level, it will continually adjust based on signals from the network, traditionally packet loss and Round Trip Time (RTT). Newer implementations of congestion control implement more complex algorithms, in some cases generated by machine learning that are far beyond anything human architects could even consider. TCP utilizes a receive window that is advertised in the header. The receive window communicates the available buffer capacity on the receiver and changes when the buffer fills. The transmitter may never have more unacknowledged segments in the network than the value of the receive window as doing so could cause an overflow of the receiver’s buffer.

In the original implementation, a TCP session could complete the 3-way handshake and immediately transmit the entire size of the receive window. For example, with a receive window of 8 * Max Segment Size (MSS) advertised, the sender could burst 8 packets over a 10 Mbps Ethernet link. At the time, the NSFNet backbone ran at 56 Kbps so a burst of 8 500-byte packets would congest a core link for over 500 msec. With this behavior and the lack of any arbitration between flows, the resulting network was extremely fragile and experienced several catastrophic failures known as congestion collapse events.

Slow Start and Congestion Avoidance

The TCP Congestion Avoidance scheme was initially proposed by Van Jacobson and Michael J. Karels after observations of congestion collapse events in the mid-1980s. Long before PSY and Gangnam Style, it was literally possible to “break the Internet” due to lack of congestion control. These were not mere degradations but drops of three orders of magnitude in usable bandwidth even for nodes separated by only a few hops. Their seminal Congestion Avoidance and Control paper [Jacobson & Karels] introduced a number of new algorithms to manage TCP congestion. The stated goal of this scheme has stood the test of time: flows should exhibit a conservation of packets:

“By ‘conservation of packets’ we mean that for a connection ‘in equilibrium’, i.e., running stably with a full window of data in transit, the packet flow is what a physicist would call ‘conservative’: A new packet isn’t put into the network until an old packet leaves.”

The two key mechanisms (Slow Start and Congestion Avoidance) from the initial paper were implemented in the 4.3.Tahoe release of the BSD Unix operating system and later became known as “TCP Tahoe”. While Tahoe is no longer widely used, it represents the first stage in the evolution of TCP congestion control.

Starting with Tahoe, each end of a TCP session maintains two independent windows that determine how many unacknowledged segments may be in transit at a time. The receive window operation is unchanged. The congestion window dynamically represents the network capacity to support the flow. At any given time, the smaller of the two windows is used to govern the number of unacknowledged packets that may be in transit. Together, the RTT and congestion window size determine the overall throughput of the flow. Releasing new segments as previous segments are acknowledged has the effect of clocking and pacing the network, and action must be taken when this clock is lost which is detected via a timeout.

The first stage in TCP congestion control was called slow start. The name is potentially misleading as it exponentially ramps up the size of the congestion window, but it doesn’t allow the sender to immediately fill the entire receive window as was allowed before. Slow Start increases the size of the congestion window by allowing an additional packet to be “in flight” every time an ACK is received – each segment acknowledged allows two new segments to be sent. Doubling the window and sending all the new segments as soon as possible results in a bursty behavior which impacts buffering requirements. The congestion window starts at some small multiple of MSS (max segment size, default of 536 or negotiated during the handshake and often 1460 bytes today) and grows by the MSS with each ACK. This algorithm results in an exponential increase in the window size so the rate can grow quickly. Increasing the window as ACKs are received makes the rate at which the window size can increase highly dependent on RTT which illustrates one of the ways that TCP behaves differently on the Internet vs. Data Center due to the 10000x difference in RTT (10s of us vs. 100s of msec).

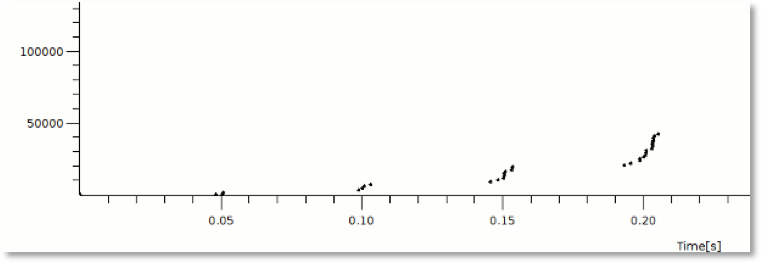

Figure 1 below shows a capture of packet transmission during Slow Start with a 50 msec RTT and illustrates the bursty nature of TCP implementations as groups of packets are released.

Figure 1 - Visualizing Slow Start packet progression with 50ms RTT (from packetlife.net)

Once the congestion window reaches a certain size called the slow start threshold, the session transitions from slow start to congestion avoidance mode. The slow start threshold is initially set to a high level. Once in congestion avoidance mode, the congestion window will increase linearly rather than exponentially – only one segment per RTT. In Tahoe, if any packet loss is detected, the session reverts to Slow Start and the slow start threshold resets to half of the congestion window at the time the loss was detected. This means the session will enter Congestion Avoidance at a smaller window size on the next ramp. A result of this mechanism (halving the congestion window) is that persistent congestion can result in an exponential decrease in the congestion window size and slow start threshold which dramatically impacts session performance.

Another aspect of TCP congestion control is determining how long to wait before declaring a segment lost due to the packet or its ACK being dropped or corrupted. This value is called the receive timeout (RTO) [RFCs 6298 & 1122]. Setting RTO too low can result in unnecessary retransmissions. Setting it too high will result in slower detection of traffic loss.

Due to changing network conditions (e.g., routing path change or congestion), the RTO cannot be set to the best case or even average Round Trip Time. Instead, a smoothed RTT and the RTT variance are calculated. RTO is set to the smoothed RTT + 4 times the variation or 1 second, whichever is greater.

For further discussion of retransmit timeout, refer to RFC 6298. In Tahoe, RTO is not set below 1 second so detecting network congestion via RTO can take a relatively long time, especially in low-RTT conditions. Later developments in TCP address this and other limitations of Tahoe.

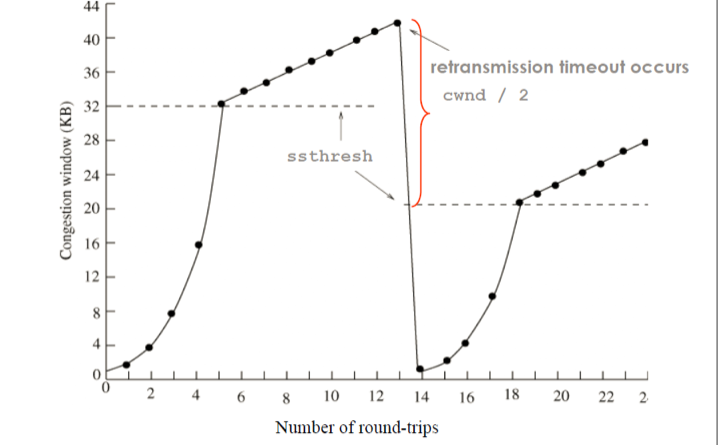

Figure 2 below shows the congestion window size during Slow Start, Congestion Avoidance, and after an RTO event.

Figure 2 - Slow start, Congestion Avoidance, and Slow start threshold adjustment after Retransmission (multiple sources, via NC State)

As part of the acknowledgment process, TCP implicitly informs the sender’s TCP stack when it receives segments out of order. This occurs when multiple ACKs are received for the same segment. The receiver is communicating that it received a new segment but still can only acknowledge the previous segment since there is a gap. This enables fast retransmit. As an example, if the receiver has segments 0-550 and receives 552 and 553, 551 may have been lost. The receiver will send a duplicate ACK for each later segment received in this scenario. This is an additional ACK for the last segment before the gap (550). This information allows the sender to retransmit sooner than waiting for a timeout. Traditionally, fast retransmit triggers retransmission after 3 duplicate ACKs. One limitation of this approach that will be addressed in later algorithms is that it depends on additional traffic after the dropped segment. In the short flows characteristic of small web objects or distributed processing results in a DC (e.g., Hadoop), it’s not uncommon for flows to be only a few MSS so there may not be 3 additional segments sent after the one that was lost. In addition, this mechanism doesn’t allow TCP to recognize when multiple segments were lost.

Finally, after periods of inactivity (roughly equal to the RTO), sessions should return to slow start. This is to prevent a session from bursting an entire large congestion window of traffic into a network whose state may have changed.

TCP Reno – Fast Recovery

TCP Reno adds a fast recovery mechanism which avoids returning the session to slow start if the loss is detected via duplicate ACKs. Instead, when fast retransmit is triggered, the ssthresh and congestion window are both set to half the current congestion window and the session remains in congestion avoidance mode. While the missing segment is being resolved, the acknowledgment of the further out-of-order segments allows new segments to be transmitted while still maintaining the allowed number of segments in flight. The duplicate ACKs do not trigger an increase the congestion window size. If fast retransmit isn’t successful, a timeout (RTO) occurs which results in the session reverting to slow start. In Reno, regular retransmission and a reset to slow start occur if more than one segment is lost within an RTT. If the same segment must be retransmitted multiple times, the RTO window will increase exponentially, and the session performance will be significantly impacted.

While other TCP options are now available, the mechanisms in TCP Reno provide the foundation for modern congestion control and retransmission. Later models mainly refine the algorithms and recovery behaviors while still following the receive window, congestion window, fast retransmission, and fast recovery model.

Leaving Nevada – More Congestion Control Algorithms

There are many other congestion control mechanisms such as SACK, New Reno, CUBIC, PRR, Vegas, BIC, Compound TCP, DCTCP, MTCP, and others. In fact, the Linux kernel 3.14.0 supports 12 different congestion control algorithms that either promise better performance overall, optimization for characteristics such as constraining latency, or for specialized environments. It is important to note that the congestion control algorithm isn’t negotiated and may be different for each host in a session. This allows for operating systems or even applications to choose different algorithms and also to set their TCP parameters. For example, the initial congestion window and initial RTO may also be set by the client. Initial congestion windows of 10-20 are now common [Wu & Luckie], and there are discussions in IETF about eliminating the initial congestion window entirely (when combined with pacing). While initial RTOs below 1 second make sense in many networks, caution should be taken as network latency is not the only factor in RTT – gateways, VPN servers, and delayed ACKs may also add latency. Selective ACK (SACK) [RFC 2018] is a TCP option that improves the default behavior of cumulative acknowledgment. Without SACK, when the host receives a duplicate ACK it cannot determine if segments other than the one directly after the acknowledged segment were also lost so it doesn’t know what needs to be retransmitted. If it just transmits the first unacknowledged segment, it will take a full RTT to identify another missing segment. The ability to selectively acknowledge segments solves this problem. SACK must be negotiated between hosts. Usage was above 90% in a recent experiment conducted by Google [Dukkipati, Mathis, Chueng & Ghobadi].

NewReno [RFC 3782] addresses the case of multiple segment loss when SACK isn’t enabled. In this case, the sender doesn’t know that multiple segments are lost until the first retransmission is acknowledged. NewReno updates the behavior for the “partial response” scenario when additional missing segments are detected after the first retransmission. NewReno is commonly deployed and is the default in FreeBSD.

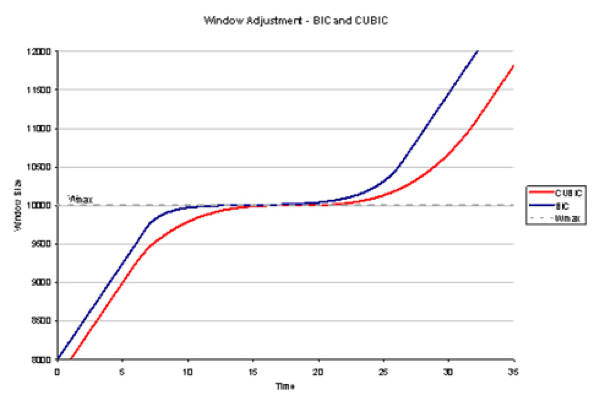

CUBIC improves the congestion control behavior of TCP on high-RTT, high-bandwidth networks while maintaining fairness among new and existing flows and among flows with varying RTTs [Ha, Rhee & Xu]. Two of the key innovations are using the time since the most recent packet loss to expand the congestion window (RTT neutral) and expanding the window with a cubic function. The cubic function allows the window to grow rapidly before the previous congestion level but more cautiously near the level where congestion was last observed. If the previous congestion is no longer occurring, the rapid expansion resumes.

CUBIC is effective for high-bandwidth high-RTT networks as the congestion window growth is not dependent on ACKs (and thus RTT). CUBIC is the default in Linux and MacOS Yosemite. CUBIC is the default congestion control algorithm in Linux and is therefore broadly deployed. As Android uses Linux, it is also deployed in wireless networks.

Figure 3 - CUBIC window expansion in red - via Geoff Huston

TCP Proportional Rate Reduction [Dukkipati, Mathis, Chueng & Ghobadi] was developed by Google to improve the fast recovery mechanism; it is used in combination with congestion control algorithms such as CUBIC. PRR smooths the retransmission behavior by pacing retransmissions and by reducing the congestion window by less than half during recovery. PPR also introduces an early retransmit mechanism which reduces the number of duplicate ACKs required to trigger fast retransmits when there are indications of a short flow that may not have many additional segments. CUBIC + PRR has been the Linux default since kernel release 3.2.

In addition to the PPR proposal, the paper contains experimental data collected from two Google data centers which is discussed later in this paper.

Compound TCP was developed by Microsoft and is the default in several of their operating systems. It is optimized for large BDP environments. It does this by estimating queue delay and adding a “delay window” to the traditional congestion window size.

Reno variations, BIC, CUBIC, and Compound TCP are all widely deployed. Their behaviors each present a different load on router buffers. This factor is addressed in [Yang, Zhang & Xu]. One of the key findings in the paper is that the newer algorithms have a lower standard deviation in the congestion window size. That implies less macro-level burst behavior from window size changes relative to earlier implementations.

Future Directions in Congestion Control

Many users now access the Internet primarily via mobile devices over cellular networks. These networks have behaviors for which traditional TCP algorithms are not optimal. First, available local bandwidth can vary dramatically and rapidly – by several orders of magnitude within seconds. Second, packet loss is less indicative of congestion than in wired networks. Recent research from MIT and Stanford [Winstein] explores alternative ways to receive “signals” from the network and leverages machine learning to derive novel congestion control algorithms based on an application’s goals (e.g., maximize bandwidth while 95% of packets have latency below 100 msec) and a range of parameters for the network. Two key innovations from Winstein’s work are Sprout which is a transport protocol optimized for video conferencing over cellular networks and Remy which is a tool to generate customized congestion control algorithms.

Sprout maintains a congestion window that is not dependent on packet drops. Instead, it predicts network capacity based on factors such as inter-arrival delay of ACKs and RTT variation. This information is communicated by a receiver back to the sender in real time. As mobile applications often communicate between two instances of the same application, they present an opportunity for customized transport protocols. Note that Sprout is not a TCP variation but an alternate transport protocol. It leverages the congestion window concept, but – unlike TCP – utilizes communication about the network state between endpoints. In simulations using traces of real-world network bandwidth (highly variable while driving around and switching mobile towers), Sprout was shown to dramatically outperform widely-deployed TCP algorithms in quickly adapting to increases and decreases in available bandwidth as well as limiting latency.

Remy [Winstein et al.] is a program that generates congestion control algorithms to fit network and application constraints. It currently operates on three variables which highly correlate to future available bandwidth. They are average inter-arrival time for acknowledgments, an average of the sender’s timestamp echoed in those ACKs, and the ratio of the most recent RTT and the minimum observed RTT on the connection. The computed algorithm then maps these into values to adjust the congestion window and pace outgoing packets. Remy is not constrained to these variables; they were the ones that showed the best predictive quality while remaining practical (around $10 of cloud computations to develop an algorithm). Remy is capable of generating congestion control algorithms for a range of network conditions and application needs. How an individual algorithm actually works is a subject for future research to reverse engineer their properties.

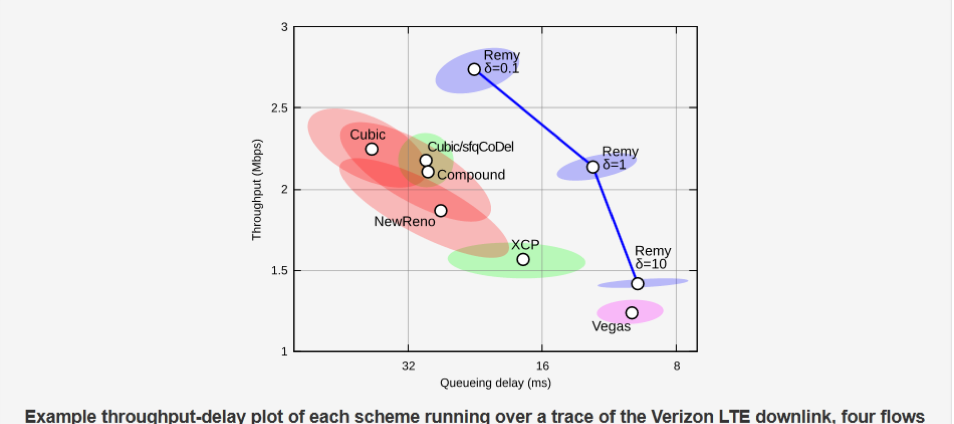

Using the Remy-derived algorithms with recreated traces from wireless networks yielded significant improvements in bandwidth and latency relative to widely-deployed mechanisms, even with AQM enabled. Unlike Sprout, Remy does not require communication of congestion information between endpoints so it can be used natively within TCP. The results from simulations of Remy algorithms (optimized for bandwidth, latency, or a balance) relative to other algorithms are shown below. The circles are the median bandwidth and latency. The surrounding ellipses show the variability (unfairness) among senders.

This approach opens a new path towards optimizing algorithms for specific applications in a range of environments, including customization for specific applications in data center, wireless, and mobile.

Figure 4 – Median and variation in latency in throughput for congestion control schemes (upper right is best) - Winstein

Packet Bursts

It is accepted that router buffering should be designed to manage “bursts” of traffic, but there is no single definition of what that means. At a high level, the term usually refers to a temporary increase in traffic that is not part of persistent congestion. For example, a link with an average of 5% utilization over a minute that is seeing output drops is likely to be experiencing bursts beyond its buffering capacity.

What constitutes a burst or defines the type of burst is dependent on the network context. From a host perspective, one case of a significant microburst would be when the host generates a large number of packets in response to a single event [Dukkipati, Mathis, Cheng & Ghobadi]. For example, if a single TCP ACK received by a 10GE- attached server communicated that a large number of segments have been lost, the sender might replace them all immediately. Wherever the interface speed is lower than 10G, they will need to be buffered even without persistent congestion.

Microbursting behavior is common any time there is an interface speed drop along the path. It also occurs with oversubscription, especially when traffic is synchronized by an application such as Hadoop MapReduce.

Usually, the desired behavior is to buffer the burst, avoid packet loss, and thus not signal the senders to slow down. In automated stock trading, the added latency from buffering even microbursts may be unacceptable, and the only solution is to increase the link bandwidth. When planning for bursts, it is important to keep in mind the pacing behavior of TCP. When there are a range of link speeds, the data packets for a flow become spread out on the faster links as the ACKs returning over the slow link clock future transmissions.

Bufferbloat

Jim Gettys has performed an extensive investigation into the interaction of buffering with TCP. His research began with real-world experience and focuses on the sources and effects of too much buffering.

This problem is highlighted in 2011 IEEE article [Gettys]. Additional discussion can be found in a group discussion on the topic [Gettys, Cerf, Jacobson & Weaver]. The central idea of the paper:

“Although some buffering is required to smooth bursts in communications systems, we’ve lost sight of fundamentals: packet loss is (currently) the only way to signal congestion in the network, and congestion-avoiding protocols such as TCP rely on timely congestion notification to regulate their transmission speeds.”

The result of not receiving timely notification is that TCP cannot operate at optimal performance, resulting in reduced throughput, high latency, and retransmissions which perpetuate congestion. Gettys’ research started by investigating multi-second latency on his home Internet connection. As he continued to untangle what was happening, he noticed that large buffers were resulting in latency that distorted TCP’s view of the network. In one case, he measured 8-second latency over what was normally a 10ms path. While this paper will focus on buffering options available via router selection and configuration, it is important to keep in mind that multiple sources of added latency (from buffers in hosts, modems, and home routers) may be occurring simultaneously, and a Service Provider cannot fully control the end-to-end behavior.

Applying Congestion Control Concepts

If a router doesn’t have “enough” buffers, it will drop packets during periods of brief congestion that the applications would have preferred to be delayed instead. Depending on the loss detection mechanism, TCP will delay the slow start ramp up, enter fast retransmission/recovery, or return from congestion avoidance to slow start. Some of these responses have minimal impact (fast retransmit within a Netflix movie) are desirable when the congestion is persistent but not when the congestion is limited in duration and subsequent packets would have been forwarded at the original rate. The Google experiment highlights the negative impact of drops on web traffic, resulting in session completion latency significantly higher than without drops.

There are also risks of too much buffering. As shown in the Bufferbloat research, TCP usually relies on the packet drop signal to limit its transmissions. Not dropping packets can result in the congestion window growing larger than is justified, further adding to congestion. Not dropping packets sends the signal for hosts to increase their transmit rate. An inflated congestion window will also prevent new flows from acquiring network bandwidth as it allows existing flows to continue sending large bursts. The delay introduced by too much buffering also distorts the RTT and RTT variance calculation which impacts the RTO timer, leading to slower loss detection.

In addition, if the packets that would have triggered duplicate ACKs are delayed in buffers, a lost packet is less likely to be detected and recovered via fast retransmission. This results in an RTO and the session returning to slow start rather than just reducing its window via fast recovery. In addition, if buffering significantly increases the RTT, performance will degrade as the sender can only transmit a set number of segments per RTT. The risks of too much buffering can be managed by configurable queue lengths, AQM techniques such as WRED, and QoS mechanisms to prioritize important traffic.

Therefore, there are risks of buffers that are too small or too large. The best size for a given link will depend on a number of factors including the place in the network (e.g., RTT, link speeds, oversubscription, flow count, and congestion) and applications as well as commercial considerations such as purchase price and ongoing expenses such as space and power.

Best-laid Plans - Of Mice and Elephants

A significant complication in network and buffer design is the variation in TCP flows. Elephants are the one- percenters of the network world and consume a large amount of bandwidth per-flow. They are relatively long-lived (many RTTs) and thus spend much of their time in Congestion Avoidance mode (reacting to signals) with large windows of segments in the network. If not managed appropriately, they can starve other flows.

Mice are short-lived, and many complete without leaving Slow Start. Elephants tend to be interested in bandwidth, while mice tend to aim for short completion times. When mice and elephants share buffers, it doesn’t always work out well for the mice, especially if the elephants are unresponsive to congestion. Large groups of synchronized mice flows have recently been referred to as lemmings. They present a unique buffering challenge in data centers in applications (e.g., Map/Reduce) where one server may launch connections to hundreds or thousands of other servers that create a many-to-one response [Baker]. Because they are short-lived, mice and lemmings don’t easily co-exist with the congestion and queue management schemes that control the elephant population. They don’t need to be slowed down as they will complete quickly, and drops can significantly delay flow completion.

In addition to filling buffers, elephants can also cause problems when multiple paths exist such as L3 ECMP or L2 bundles. If too many of the elephants hash onto the same link, significant congestion can occur even when there is available bandwidth remaining on other links.

Not all individual flows are elephants or mice. HTTPv2 supports low-volume long-lived sessions so that a new socket isn’t created as often. In this case, TCP should still respect the guideline of reducing the congestion window after periods of inactivity.

The presence of mice, elephants, and lemmings, and their behaviors are one of the reasons it is difficult to make any generic recommendations for data center networks. Research is ongoing into the best way for these different types of flows to co-exist. Solutions such as scheduling, dividing, or recognizing and steering elephants are being explored.

TCP Summary

TCP responds to packet loss by returning to slow start (RTO detection), halting window growth (during fast retransmit with unresolved segments), or reducing the congestion window (fast recovery). Packet loss is not inherently detrimental to a network transporting TCP traffic. In fact, with currently deployed congestion control algorithms, it is a necessary tool for TCP to function properly in the presence of congestion. When segments can be recovered via SACK and fast retransmission, segment loss may not significantly slow down the overall throughput of the session relative to the requirements of most applications. Packet loss detected via RTO is more detrimental as it will return the TCP session to slow start. Multiple RTOs is the worst case and should be avoided if at all possible since it dramatically will slow down the session. Infinite buffering does not prevent RTOs, but it may prevent fast retransmission by delaying later packets.

TCP is also responsive to signals other than packet loss. When persistent buffering occurs in the network, TCP responds to increasing RTT and RTT variance by increasing the RTO. This slows future detection of loss via RTO timeout.

With regard to designing a network for TCP traffic, the goal should be well-managed buffers and appropriate packet drops as defined by application requirements. The ideal amount pf buffering for different parts of the network should be determined by a combination of applications, bandwidth, round trip time, and traffic characteristics.

Academic Research on Buffering

The most-cited early paper in buffer sizing is “High Performance TCP in ANSNET” by Curtis Villamizar and Cheng Song in 1994. The paper explored the buffering required to maximize link utilization with a very small number of long-lived TCP flows. With a small number of sessions, packet loss may result in all the sessions returning to slow start at the same time and thus all sessions increasing their rates exponentially at the same time. When congestion occurs again, the sessions become synchronized and repeat the cycle of TCP synchronization.

The key conclusion was that the bottleneck link utilization is maximized with buffering sized to the product of Bandwidth and Route Trip Time. This value is referred to as the Bandwidth Delay Product (BDP). For example, a 10 Gbps link that is part of a path with a total RTT of 0.2 seconds would have a buffer of 2 Gigabits or 250 MB. To their credit, the authors recognized that an increased number of flows would lead to different results. More recently, Michael Smitasin of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and Brian Tierney of Energy Sciences Network (ESNet) reaffirmed benefits of large buffers for “very large data transfers with large pipes and long distances between a small number of hosts”.

Villamizar and Song provided valuable insight into the interaction of buffering with TCP. Unfortunately, the recommendation from this specific case became dogma for many years and resulted in over-building routers and over-provisioning network buffers in places where their conditions don’t apply.

Stanford & Georgia Tech

The High Performance Networking Group at Stanford, led by Nick McKeown, has been the source of significant research into many aspects of networking. Guido Appenzeller’s 2005 thesis “Sizing Router Buffers” provides valuable insight and a statistics-based approach to buffer sizing for Internet core routers with many flows. A more concise starting point to review his research is available in a Sigcomm paper [Appenzeller, Keslassy & McKeown]. With many flows, traffic may be unsynchronized, resulting in an aggregate smoothing effect and thus require less buffering. The key recommendation from this research is that buffers should be sized based on BDP and the number of long flows (TCP flows not in slow start) going through the link. Specifically: BW * RTT / sqrt (n) where n is the number of long flows. Note that n also introduces a way to represent application characteristics as different applications (video vs. small web object downloads) may vary in how much time they spend in Congestion Avoidance. This is important as many TCP flows never leave slow start.

Appenzeller’s studies and simulations focus on core links, but the general idea of proportionality between buffers and flows can be applied in other situations. For example, the core-facing uplink of an edge router may have a medium number of flows and thus require less buffering than the customer-facing link on the same router which may have all of its bandwidth consumed by a single flow.

Subsequent papers from researchers at Georgia Tech [Dhamdhere & Dovrolis] [Dhamdhere, Jiang & Dovrolis] argue that while the Stanford Model is effective for achieving high link utilization, it may result in significant packet loss (5-15% in simulation) in some situations. They contend this amount of packet loss then leads to high levels of retransmissions and reduced application performance.

The Georgia Tech research introduces several new concepts. First, it suggests that links be classified as to whether or not they are “saturable”. Even without going further into the research, this concept is important for practical applications of buffering design. For example, if a particular Data Center environment allows additional links to be added at relatively low cost, buffering can be limited to a level needed for speed matching and microbursts as persistent congestion can be avoided. On the other extreme, a DSL, cable, or wireless “last mile” may experience significant persistent congestion. Their research agrees with the Stanford Model that “small’ buffers are sufficient for backbone links, but for a different reason: not being saturable based on current Service Provider deployment practices.

The Georgia Tech research also states that any conclusions based on the number of TCP flows must limit the counting of flows to long TCP flows that are not bottlenecked at other links and not bottlenecked by the end hosts windows or attachment speed. They also present calculations in which they show that in the Stanford Model the loss rate increases with the square of the number of flows bottlenecked at that link.

Another paper by Georgia Tech and Bell Labs [Prasad, Dovrolis & Thottan] seeks to find the buffer size that maximizes the average per-flow TCP throughput. Their conclusion is that this is primarily a function of the output/input capacity ratio, which is defined as output capacity relative to peak cumulative input flow size (not just local ingress bandwidth but also taking into account the sources of the flows). Their results support the view that buffers can be significantly smaller than BDP when a link carries many flows but also propose that values closer to BDP are be merited in some cases.

A 2006 paper from Stanford [Ganjali & McKeown] addresses the Georgia Tech findings and proposes a heuristic for core links which represents a compromise.

“And so for now, we would cautiously conclude that at the core of the Internet, where the number of flows is very large, the buffers can be reduced by a factor of ten, without expecting any adverse change to the network behavior; in fact, we would expect delays and delay variation to be reduced.”

With the Internet RTT of 250 msec, this “factor of ten” results in 25 msec buffers for a router serving the global Internet core. Networks primarily serving regional or intra-continental traffic will need proportionally smaller buffers.

The collective research supports the argument that buffering requirements depend on many factors including the desired outcome (e.g., keep link fully utilized, limit loss, or maximize per-flow throughput); the levels of oversubscription and congestion; and the number, type, and synchronization of flows. That’s before considering the sensitivity of applications to loss, latency, and jitter. While the research doesn’t provide a single answer, it opens up some new ways to look at the problem and to evaluate alternatives in the context of their place in the network. There is less research on edge and access buffer sizing, but what is available tends to support the idea that in locations where a single flow can take all of a link’s bandwidth that BDP-sizing may be needed for that link. If buffers are shared, the aggregate buffering may be reduced.

Other Views

Many of the research models rely on the assumption that packets arrive in a Poisson distribution (arrival time is not dependent on other packets). In [Nichols & Jacobson], the case is made that pacing via ACKs creates standing queues and non-Poisson packet arrival. They also reference [Vu-Brugier, Stanojevic, Leith & Shorten] which is critical of smaller buffer proposals and experiments and advocates BDP buffers based on simulations. Another reality is that business considerations may override the desire for an ideal design. Routers with small on- chip buffering can be significantly denser, much less expensive, and consume less power that routers with deeper off-chip buffers.

The factors discussed in this paper should help assess where underprovisioning the ideal with have more or less impact.

Real-world Buffer Experiments and Data

Stanford, University of Toronto at Level 3 – Core Buffer Sizing

In [Beheshti et al.] researchers from Stanford and the University of Toronto were able to conduct an experiment in the Level 3 commercial backbone. A set of 3 parallel load-balanced (4-tuple flow-based) OC-48 links with very high utilization (over 85% for 4 hours per day) were configured with varying amounts of buffering and monitored. The researchers calculated an average of 10,000 flows per link. The default buffer size was 190 msec (60 MB or 125,000 500B packets), and no Active Queue Management (AQM) mechanisms were in use.

The buffers for the 3 links were reconfigured with one link always set to 190 msec and the other links set to two of the experimental values (1, 2.5, 5, or 10 msec). Each buffer size was evaluated for at least 5 days. No drops were seen with the 5, 10, and 190 msec buffers for the entire duration. Packet loss in the range of 0.02% to 0.09% was seen with 2.5 msec of buffering and correlated to the link utilization. There was a relatively large increase in packet loss with 1 msec of buffering, but link utilization was still maintained. Most of the loss occurred when the link utilization was above 90% for a 30-second average. The packet drop level for the 1 msec buffer was still below 0.2%.

These experiments support the Stanford model for core buffering requirements and support the theory of highly- smoothed traffic when many flows are present.

Facebook – Link and Buffer Utilization

Researchers at the University of California at San Diego recently performed in-depth analysis of traffic at Facebook [Roy, Zeng, Bagga, Porter & Snoeren]. Their paper includes a range of findings, many of which are relevant to buffering design.

Servers were 10G attached and average less than 1% 1-minute link utilization, 90% are under 10% utilization.

As seen in other studies [Kandula, et al.], Hadoop traffic exhibits extremely high rack locality – most of the traffic is between the master and slave in the same rack. Hadoop flows are short. 70% send less than 10 KB and last less than 10 seconds. The median Hadoop flow is less than 1 KB and 1 second and thus doesn’t ever enter congestion avoidance. Only 5% exceed 1 MB.

Data on buffer utilization was collected at 10 usec intervals for links to web servers and cache nodes. Even with the low aggregate utilization, the buffers were constantly in use on the ToR switches (Facebook Wedge with Broadcom’s Trident II ASIC, which has 12 MB of shared buffers).

“Even though link utilization is on the order of 1% most of the time, over two-thirds of the available shared buffer is utilized during each 10-us interval.”

Google – Initial Congestion Window

Google [Dukkipati, et al.] conducted experiments to investigate the effects of increasing the TCP initial congestion window to 10 segments or higher. They found a substantial increase in the number of web transactions that could be completed within one RTT and a corresponding decrease in completion time. The negative effects of this change were limited and acceptable in most cases. They propose this approach as an alternative to opening large numbers of parallel TCP connections. Data from CAIDA [Wu & Luckie] shows that many large sites are now taking this approach with 60% having an initial congestion window between 10 and 16 segments. This evolution of TCP does illustrate that the underlying flow behavior of traffic may change over time even if the traffic itself does not and provides a motivation for allowing some room for change when selecting hardware, especially towards the edge and access layers of the network where there are a smaller number of flows.

The evolution of the initial congestion window since the referenced buffering research at Stanford and Georgia Tech and experiments needs to be taken into account when applying the conclusions today. The common TCP stacks prior to recent developments used an initial window of 2-4 segments [RFC 3390]. In 2010, Google proposed an initial window of 10 [Dukkipati et al.], and it has been widely adopted. As the congestion algorithm and settings are independent for each sender and most traffic is server-to-client, it only takes a small number of top providers to adopt this change to dramatically change the aggregate TCP behavior on the Internet. [Wu & Luckie] shows that 60% of the Alexa 10K sites are now using an initial congestion window of 10 or larger.

Google – Packet loss, session latency, and Proportional Rate Reduction

In the proposal for Proportional Rate Reduction [Dukkipati, Mathis, Cheng & Ghobadi], Google presents significant real-world data on TCP behavior in two data centers. One was in the US providing multiple services to the east coast and South America, and a second DC was in India serving Youtube exclusively. Some of the highlights are:

- There was an average of 3.1 HTTP requests per connection

- The average HTTP response size was 7.5 KB (5-6 segments, within the increased initial window sizes)

- 6.1% of HTTP responses have TCP retransmissions

- Sessions experiencing loss had 7-10 significantly longer completion times than the ideal

- 2.8% of TCP segments are retransmitted with 2.5% for the US DC and 5.6% for the India DC

- 54% of India DC retransmits and 24% of US were fast retransmits

- An average of 3 retransmissions per fast recovery event (loss is correlated)

- Sessions connecting to the India DC spent just under half the total time in a loss recovery mode

- Sessions in the India DC had an average RTT of 860 msec

These figures show that packet loss and RTOs are quite common. The former appears inevitable. The latter could potentially be improved if losses were less correlated (via AQM mechanisms improving the drop behavior) and thus more easily recovered. The India RTT is surprisingly high and is an indication that bufferbloat and heavy levels of congestion are occurring along the path. It also demonstrates that even very large amounts of buffering do not prevent packet loss.

The high India RTT raises the question of whether nominal or actual latency should be considered when using RTT as part of a buffer sizing calculation. The actual RTT determines TCP’s responsiveness to congestion, but such high variation makes it difficult to use in sizing.

In these experiments, PRR was able to reduce session latency by 3-10% compared to the standard Linux recovery mechanism at the time. PRR is now the default [as of 2015] for fast recovery in Linux, where it is combined with the CUBIC congestion control algorithm.

Application Requirements

Applications have a wide range of requirements from the network and they all have preferences for the network’s behavior. Starting with the most latency-sensitive applications, a range of requirements are presented below.

High-Frequency Trading

High-frequency Trading (HFT) is a well-known latency and PDV-sensitive application. Financial service providers have literally moved mountains at a cost of hundreds of millions of dollars to shave several milliseconds of propagation delay [NY Times]. In a pursuit of money that would make Austin Powers’ Dr. Evil proud, others have used a sophisticated heat beam called a “laser” to minimize delay between the New York Stock Exchange and New Jersey data centers. [WSJ]. Add in co-located servers with dedicated cores that are replaced quarterly, low- latency NICs, kernel-bypass drivers, and the “race to zero” (latency) has may have reached the point of diminishing returns with regard to nominal latency. Innovation is now occurring even at the protocol level – moving from a human-readable flexible format to binary data that can be parsed more quickly by a computer.

In that context, it’s clear that all possible nominal device latency must be eliminated and buffering minimized. This can be done by minimizing the number of memory operations and the use of cut-through switching in which frames are transmitted on one fiber while still being received on the other. These transactions don’t consume a large amount of bandwidth, so the general approach to designing these networks is to overbuild them to the point where congestion of any kind is unlikely.

Gaming

Gaming comprises a range of applications with different requirements. Many of them have a latency constraint, and it is mostly important to avoid high latency rather than to minimize latency. In addition, the financial drivers are different and gaming-optimized service offerings from ISPs are minimal. More bandwidth, QoS-capable home routers, and keeping your house mates off Netflix are often the only options an end-user has to improve their gaming experience.

Game setup and chat are mostly performed with TCP and don’t have strict latency requirements. Gameplay usually operates via UDP. Gameplay requirements depend on the type of game (e.g., first-person shooter or real-time strategy) and the precision required for an individual action which is dependent on the location of another player (e.g., sniper rifle vs. throwing a grenade in a first-person shooter). A good introduction to requirements for gaming can be found in an ACM paper from researchers at WPI & MIT [Claypool & Claypool].

Most online games have relatively low bandwidth requirements (10s of kbps) and tolerance for latency of around 150-200 msec. Round-trip latency is called “ping” in gaming circles and is often displayed when selecting potential opponents. Most games have techniques to mask latency up to this level by allowing the client to predict the result of their actions. For example, the character may move and display an animation while a sound is played. If the server later disagrees on the game state, a correction to the state is made. If a correction is required, the client will rerun everything that occurred after the corrected information, possibly resulting in a “jump” in the game as seen by the client.

To scale and manage latency, major games will have sets of servers distributed geographically as a single hosting location could not meet these requirements for everyone. For example, Blizzard has US, Europe, and Asia sites for their Battle.net service which hosts World of Warcraft, Heroes of the Storm, and Starcraft. This still doesn’t allow for much buffering as uncongested ping may reach 150 msec in Asia or between South America and the US. In the US and Europe, uncongested latency is mostly under 100 msec. Gaming, therefore, is unlikely to benefit from aggregate buffering beyond 50 msec for an individual flow.

Non-live Streaming Video

Video was 64% of all consumer Internet traffic in 2014 and is predicted to reach 80% in 2019 [Cisco]. Netflix, YouTube, and sites using similar streaming technologies generate the vast majority of the video traffic so their applications will provide valuable insight into video requirements.

Netflix and YouTube stream video over HTTP (TCP) and are normally capable of sufficient host-side buffering to retransmit lost packets and tolerate moderate increases in latency. Note that there is variation among clients and mobile devices will have distinct characteristics. Unless there is significant packet loss, overall quality is primarily a function of bandwidth. When the host-side buffer is empty, the video pauses to rebuild the buffer. This is referred to as “buffering” by users. On YouTube, the current depth of the host-size buffer is visible with a gray bar showing much of the video has been received.

Both are capable of dynamically adapting video quality to bandwidth. Initial startup time is also important – more so for Youtube as users are watching shorter videos rather than sitting down to watch an hour at a time. Prior to 2012, YouTube would transmit what was effectively a single large file specific to the chosen resolution. Packets were buffered in the application, and the video would pause when playback exhausted the buffer. In 2012, YouTube moved towards a new model (Sliced Bread) which allows for shifting between resolutions as network conditions changed. Further innovations such as preloading slices of related videos also improve performance during times of reduced network capacity [gizmodo].

Once the host-side buffer has been built, non-live streaming video is tolerant of most network conditions other than losing connectivity or bandwidth for an extended period of time (enough to exhaust the buffer, often several seconds). Single-packet loss is well tolerated as lost packets can be retransmitted via fast retransmit, and TCP enables packets to keep flowing while the loss is being resolved. With sufficient host buffering, limited RTO events may also be tolerated without impacting end-user experience.

Most users access Netflix and Youtube via CDN caches rather than a central location. For example, Netflix is present in almost every colocation facility in the US so uncongested RTTs are often under 20 msec. Given the volume of video, this significantly impacts router buffering requirements. If most of the traffic passing through an edge router is destined to a video cache with an RTT in the sub-20 msec range, TCP will respond more quickly to loss than the traditional assumption of max RTTs (250 msec). Therefore, a weighted RTT may be considered in hardware sizing on edge routers as long as signals are sent to the hosts in a timely manner.

Live Streaming Video

Live video is more demanding as host-side buffering isn’t able to mask suboptimal network conditions. UDP is usually used as retransmits would arrive too late to be of value. Live video is inherently bursty due to video compression algorithms which don’t need to send as much data when there is less motion. Live video may comprise video conferencing, sports, viewing gaming, and other applications. The required and available bandwidth may vary dramatically. On the high end, Cisco Telepresence uses around 5 Mbps per direction in the highest-quality 1080p mode [Cisco]. Telepresence recommends a maximum of 150 msec of latency. The deployment guide suggests that users will perceive latency at levels from 250 to 350 msec. Live streaming is also sensitive to packet delay variation (PDV). In Telepresence, the “jitter buffer” is initially set to 85 msec and may increase to 245 msec if needed. Packets that are dropped or arrive late (beyond the jitter buffer) result in video pixelization.

At 1080p, the uncompressed video stream is 1.5 Gbps and the compressed stream is 4 Mbps. Therefore, each packet contains a large amount of video data. Cisco recommends a loss target (including late packets) of 0.05%. In corporate networks, services like Telepresence should receive priority treatment in the network.

Other video conferencing applications such as Skype need to live with available bandwidth and adjust their requirements to what is available, often very rapidly. They will suffer similar issues with packet loss, latency, and delay variation.

Voice over IP

VoIP typically uses TCP for setup and UDP to transport packets for the call. VoIP uses relatively low bandwidth and is sensitive to loss, jitter, and latency similar to video. These characteristics make it a good candidate for priority treatment in network designs where traffic is differentiated. Guidelines for maximum latency are usually between 150-250 msec with loss requirements below 1%. Without any prioritization, VOIP such as Skype over commodity Internet may have highly variable quality depending on network conditions. VoIP should not be subject to significant added latency due to buffering.

DNS

DNS primarily uses UDP for name resolution. This provides a faster response by avoiding the TCP handshake which enables requests to complete in a single RTT. As it is a relatively simple transaction, TCP isn’t required – DNS can just try again or use another server if a response isn’t received. DNS, therefore, doesn’t usually need any special treatment in the network, but excessive queuing can impact user experience and should, therefore, be minimized. Latency for DNS can also be managed by offering regional DNS servers. Finally, DNS servers are often targeted by attackers and are therefore subject to unusual traffic patterns outside normal assumptions made for queuing.

Web

Web browsing makes up the majority of Internet transactions. The total bandwidth is less than video, but there are many smaller flows. Web traffic includes HTML, CSS, Javascript, graphics, flash, and other types of content. While average access speeds continue to increase, the size of the average web page continues to grow as well. In 2010, the average for the top 1000 sites was 626 KB; it is now over 2 MB [httparchive]. In theory, without any server or bandwidth constraints, 2MB takes 8 RTTs for the Reno algorithm with an initial window of 10 (14.6 KB in the 1st RTT, 29.2 KB in the 2nd. . . 934 KB in the 7th , and 1.9 MB in the 8th). In reality, full page loads average roughly 7 seconds for wired and often over 10 seconds on mobile devices. The higher end of this range can lead to significant abandonment, which must be minimized.

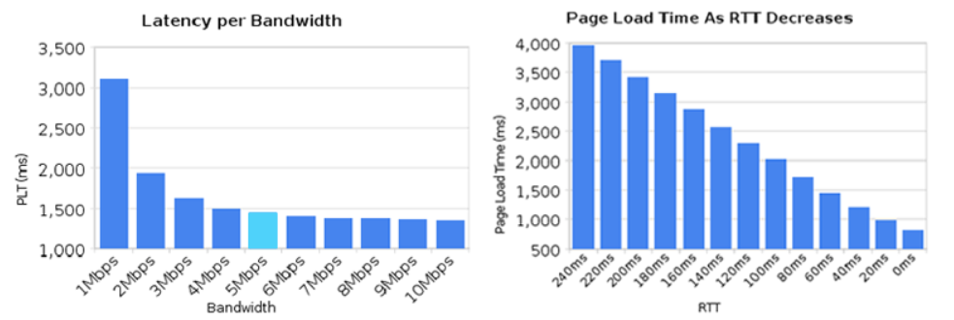

Once a sufficient level of bandwidth is available, page load times are improved by reducing RTT more than adding additional bandwidth. This drives placement of content as close to the end client as possible. The chart below from Igvita shows the impact of increasing bandwidth and lowering RTT on page load times.

Figure 5 - Page load times with varying bandwidth and RTT

Efficiently transporting web content requires content, server, and client optimizations. Content (image compression and page structure) is likely the greatest and lowest-cost area for improvement, but the network can help mask bloated content. On the client side, most browsers open multiple TCP sessions in parallel. This allows multiple objects to be downloaded at once but doesn’t allow the client to assess the pipe capacity and adjust to drops. From the network’s perspective, it also subjects resources to multiple sessions from the same host executing slow start in parallel (and often never reaching Congestion Avoidance), which defeats the congestion control algorithm assumptions. SPDY is a protocol that reduces page load times via compression and by allowing multiple operations to happen in parallel. Rather than waiting for each object to complete before requesting the next, all the requests can be made at once and the server can return the objects as they are available and in a prioritized manner. Together, SPDY and larger initial congestion windows mitigate the need for large numbers of sessions. HTTP/2 implements this approach and will supersede SPDY. HTTP/2 will require upgrades on both client and server.

On the server side, larger initial congestion windows reduce the session completion time, and newer TCP algorithms like CUBIC and Compound TCP allow faster window growth in high-RTT networks. As the majority of traffic is sent from the server back to the client, only the server’s TCP algorithm needs to be updated for the majority of benefits to be realized.

HTTP/1.1 as deployed (parallel sessions) isn’t very buffer-friendly for the reasons above. It results in hosts not transmitting accordance with the assumptions TCP is built upon. As HTTP/2 becomes more widely deployed, more hosts will open fewer sessions and use them to transport more segments per session. This should have the net effect of reducing buffer requirements.

Peer to Peer

Peer to peer protocols such as BitTorrent are used for a variety of purposes. While it is best known for piracy, it is also used to download game updates by companies such as Blizzard, to distribute scientific data, and to distribute Linux. Without peer to peer, it would be difficult to make large files available for free. For a protocol with such a bad reputation, BitTorrent is actually very respectful of network resources. Current implementations use the Micro Transport Protocol (uTP) which runs on UDP. uTP uses the Low Extra Delay Background Transport (LEDBAT) method to avoid adding to network congestion. It is a delay-based algorithm that slows down when added latency is detected. LEDBAT can also be used with TCP for lower priority tasks such as software updates (Apple).

Data transferred via peer to peer doesn’t normally have session completion constraints or expectations of guaranteed bandwidth. Therefore, peer to peer traffic doesn’t need any special consideration for buffering.

Distributed Compute and Storage – MapReduce, HDFS

Hadoop is an example of an application’s behavior resulting in distinct network traffic patterns. Hadoop uses TCP and expects the distributed operations to complete by a certain deadline and may ignore late responses which can result in an incomplete or suboptimal result. Hadoop relies on parallel computation on multiple nodes in a cluster which then return the results to the Master. This results in both high “rack locality” (traffic stays within the rack) and synchronization of traffic that may result in TCP Incast [Chen, Grifit, Zats & Katz]. Incast is congestion caused by many-to-one responses triggered by an application. In this case, the congestion is not due to persistent high traffic or random collisions, but is the intrinsic behavior of the application.

For traffic belonging to short flows, it is preferable to buffer rather than drop and retransmit. There may be no other data beyond the initial burst, and thus nothing to react to the “signal” of packet loss. This buffering can occur in the network or it can occur on the servers themselves. Buffering on the servers is already occurring when there is more data than TCP is allowed to send immediately. Newer TCP mechanisms may leverage this capability by using pacing and jittering to take advantage of these buffers which may be preferable to adding additional buffering on the router or switch. Another aspect of the solution is to increase link speeds and thus reduce the amount of oversubscription that occurs. The best solutions to Incast are still being researched and debated.

Router Buffering Architectures

Off-chip vs. On-chip buffering

One of the tradeoffs a router architect needs to make is whether to buffer packets in memory inside the NPU / Forwarding ASIC or in a memory external to the lookup engine (or connected to a separate queuing chip).

On-chip buffering minimizes power and board space but doesn’t allow for very large buffers. On-chip buffering allows for denser routers and switches as it allows more of the ASIC’s resources to be used for physical ports. As an example, a high-scale deep-buffer Network Processor may allocate I/O pins roughly equally among off-chip FIB, off-chip buffers, fabric connections, and interface connections. In contrast, a System on a Chip router may allocate almost all of the ASIC I/O capacity to external interfaces. This is one of the key factors underlying the wide range of port counts and power consumption of routers today. Fabric-capable forwarding chips with off-chip buffers currently range from 200 to 700 Gbps while SoC models shipping in 2016 range up to 3.2 Tbps.

With off-chip buffering, there are two key requirements that must be met. First, the memory must be large enough to buffer the required packets. Second, it must be fast enough to maintain the forwarding rate. While not as challenging as FIB memory requirements (extremely high operations per second), the latter can be a challenge as commodity memories are not designed for the speed of networking applications. Therefore, custom high- performance memories or a large number of commodity memories are usually the only options to reach the memory bandwidth requirement. In addition, memory parts may not be available in the sizes for optimal buffering (e.g., a home router with 64MB when 64KB would be optimal). In these cases, it is important that vendors allow queue sizes to be limited via software configuration.

Custom memories can be made to a wide range of specifications, including bandwidth, operations per second, capacity, and physical size. For deep buffers, a router architect must choose between high-speed custom memories or large banks of commodity memories. Custom memories save board space but are significantly more expensive. They may also incur significant hardware development expenses (Non-Recurring Engineering) internally or to a vendor. Off-chip buffering with commodity memory is less expensive but often requires much more board space than custom memories due to the need to overprovision the memory size in order to get sufficient memory bandwidth. Using a higher-performance commodity memory such as graphics memory (e.g., GDDR5) helps, but still doesn’t provide the speed and efficiency of memory designed specifically for the application. A good public technical presentation of custom vs. commodity memories is presented in Juniper’s blog announcing products with the HMC Hybrid Memory Cube from Micron. Cisco uses similar fast custom memories on the CRS, NCS 6000, and Nexus platforms.

As of 2016, on-chip memories current range from 10s to low 100s of MBs, while off-chip may go up to 12 GB for a 200G Network Processor. This is roughly the same ratio as the RTT variation between Data Center and Internet traffic flows.

One goal of the very-small-buffering research is to explore the feasibility of routers in which packets are never converted into the electrical signals but instead perform operations in the optical domain. One of the Stanford papers explores the impact of the “few dozen” buffers that are becoming feasible with optical memories [Beheshti et al.].

Platforms

Buffering may occur at any point of congestion, most commonly Forwarding ASICs, switch fabrics, and egress interfaces. There are several common architectures that facilitate different buffering schemes. They differ in the size and location of buffers, how the buffers are allocated, and their queue management mechanisms. No single architecture is superior in all cases. Bigger is not always better, and there are tradeoffs that impact other areas of design such as density and power.

The most common router buffering architectures are:

Single-chip systems with small on-chip shared memory (ASR 920, RSP2, NCS 5000)

Single-chip system with deep buffers (RSP3, NCS 5501, ASR 1000)

Multiple forwarding chips with fabric interconnect and VOQ buffering (NCS 5502, modular NCS 5500), Arista 7500)

Multiple forwarding chips with fabric interconnect & VOQ and full egress buffering (GSR, Juniper PTX/MX)

Multiple forwarding chips with ingress & egress buffering (CRS & ASR 9000)

Multiple forwarding chips with small on-chip buffers and Ethernet fabric (Insieme, several Arista models)

Single forwarding processor with central on-chip buffer – By number of chassis, the most common router and switch buffering architecture is a central on-chip shared memory that can be used for ingress and egress queuing for any port. A small amount of memory is usually allocated to each interface on ingress as a FIFO for incoming packets, a small amount is assigned per-port for egress, and the remaining memory can be flexibly allocated to egress for ports experiencing congestion. As on-chip memories are relatively small today, these devices work best in environments without congestion (microbursts only) or with low RTTs. They are popular for high-volume applications such as Top of Rack due to their simplicity and low cost. Note that “small” on-chip memories in the range of 10s of MB are able to provide significant buffering in low-RTT environments as the low RTT allows long- lived flows to react quickly to congestion.

An extension of this architecture is adding deeper off-chip buffers to the single-chip system. This is often used for access or smaller edge devices such as the ASR 1000 that require WAN buffering but do not require the scale of a modular chassis.

Virtual Output Queues – To scale a router beyond a single forwarding node, the nodes must be connected via a fabric. This may be a set of fabric chips to forward frames or cells among the nodes or a mesh directly connecting the forwarding processors. The fabric may introduce another potential source of congestion. This can be solved in a number of ways including scheduling and buffering or speedup. Some early fabric-based routers suffered from head of line blocking in which packets going to a congested egress card or interface blocked packets going to other destinations from being sent. This is analogous to a car trying to turn in traffic preventing other cars going through an intersection where there is only one lane. This problem can be solved with Virtual Output Queuing. In a VOQ model, separate queues are created on ingress for each output queue. Packets may then be dequeued for any destination without blocking other queues. VOQs may be used solely to manage switch fabric congestion with separate egress queues or they may be the primary buffers on the router.

With VOQ-only models, the ingress traffic manager may or may not be aware of the depths of the queues on other VoQs. If it is unaware of the status of other queues, the total max buffering is the sum of all the available buffers on forwarding chips buffering packets for that destination. For example, if the VoQs are configured for a 20msec buffer and traffic to the congested queue is buffered on 10 forwarding chips, the total buffering may reach 200msec, which is usually detrimental to the network. In cases with a congested high-volume destination, even more buffering may occur as some currently-shipping routers have up to 96 forwarding ASICs.

Egress Queuing – Like VOQs, egress queues may have multiple roles in different routers. In a system where VOQs are the primary queues for congested interfaces, the egress queues may just be small FIFOs to reassemble and smooth the traffic to the link speed. In this case, the egress queues don’t have a significant buffering and may be placed on-chip.

Other systems use the egress queues to provide the primary buffering for interface congestion. In this case, a full set of Active Queue Management and Priority/Shaping behaviors may be implemented. All things being equal, having all the outgoing packets for a port in a single set of egress queues is preferable to multiple VOQs since it allows more visibility when performing operations that depend on queue depth. At the same time, a VOQ design can still effectively implement QoS policy very effectively, and some VOQ systems can provide global visibility into queue depths on other modules, thus allowing AQM decisions with global visibility.

Ingress & Egress Queueing was – Routers may have both ingress and egress buffering. In this architecture, the ingress buffering serves to manage any fabric congestion as well as oversubscription of any egress resources (e.g., the egress packet processor, not the output queue). Ingress buffering may be triggered via backpressure or request/grant mechanisms. It is possible to minimize ingress buffering by having sufficient “speedup” in the fabric to effectively eliminate the fabric as a source of congestion. With speedup, the fabric has higher egress capacity than ingress capacity and therefore allows multiple senders to send high rates of traffic to an egress card at the same time.

In addition to the visible buffers, small amounts of buffering are often used to smooth out the transition of packets from one stage of the router to the next. For example if one chip can send bursts at 11 Gbps and the other can receive at 10 Gbps, a small buffer is used to address the speed mismatch. These are usually FIFO buffers. They will contribute to the nominal latency as each memory copy into a buffer adds serialization delay. Minimizing the number of FIFOs is therefore important in ultra-low latency applications. For WAN or edge applications, the FIFOs are much smaller than interface congestion or propagation delays and are therefore less important for routers in those roles. This type of buffer may also be used between the input interface and the forwarding chip and some routers can prioritize traffic at this stage via preclassification and non-FIFO queuing.

Buffer Efficiency, Carving, and Sharing

The usable buffering capacity of a router is not equal to the sum of the memory components or the value listed on the data sheet. Some factors that must be considered in calculating practical capacity are buffer sharing, number of buffers, and packing efficiency. Buffer sharing may have physical or logical constraints. An example of the physical case is that egress buffers on one line card cannot be used for ports on another line card. Similarly, a line card with multiple Network Processors usually will not share buffering resources among them. An example of a logical constraint is the common approach of allocating some fixed memory to each interface and then the remaining memory into a shared pool.

In addition to constraints from the size of memory, there may also be limitations on the number of buffers (often called packet descriptors) and the efficiency of buffer use. For example, if a router has 1 GB of memory for a queue and 1 M packet descriptors, the average size of an individual buffer will be 1 KB. If the average packet size is 250B and fixed 1 KB buffers are used, the effective buffering is limited to 250 MB. Routers may have fixed-size buffers, variable-sized buffer pools (e.g., 64 bytes, 128 bytes, 256 bytes, 1500 bytes …), “chunks” where a packet may use multiple buffers. These need to be taken into consideration when evaluating usable buffering capacity.

Evolving Hardware Models – Hybrid Buffering