Service Assurance: A Guide For The Perplexed, Part Three

In Part Two of this series on Service Assurance, I reviewed the methods, protocols and tools available for active assurance of services. In this part, I want to look some high level design options to help guide your deployment. I call these:

- Do nothing

- Do everything

- Do something

The Do Nothing Approach

Service assurance can be a complex undertaking. One option is to do nothing: build a solid network with plenty of redundancy and lots of extra capacity, monitor for network performance and faults (“Network Assurance”) and have faith that the architecture can deliver the needed SLAs. This is a simple approach that can deliver value in a well-designed network. Because IP networks in general and services in particular don’t come with any built-in mechanisms for assurance, many operators start here by necessity. But this “best-effort” approach to service assurance has several weaknesses:

If an SP can’t measure the latency or jitter of a service, they can’t sell more expensive low-latency or jitter-bound services. For lack of assurance, money is left on the table.

The end customer knows more about the quality of their service and can detect impairments long before the SP is even aware of a problem.

Troubleshooting a faulty service requires a lot of legwork on the part of smart (i.e. expensive) network engineers. When the number of services is small and commands a high price, that isn’t a big problem. But as Cloud and Video push bandwidth demand ever higher, that approach to services won’t scale.

The cost of over-engineering excess capacity may exceed the cost of a good service assurance solution.

The Do Everything Approach

If “do-nothing” isn’t working out, then there’s always the “do-everything” approach, by which I mean assuring every service individually.

As a first option, you should investigate the built-in Y.1731 or TWAMP capabilities at the PE (or even CPE, if the CPE is provider-managed). Since the capabilities are built-in to the router, this is the most cost-effective approach. The important thing to verify is that supported probe scale (number of probe sessions, number of simultaneous probes) matches the required service scale on the CPE or PE. Probe scale varies widely by silicon and software release, so get specifics.

If your routers don’t support the scale or protocols you need, you can deploy an external NID or SFP to generate probes. An in-line deployment (where the NID or SFP is directly in the service data path) gives the most accurate measurement but could introduce forwarding issues of its own. This approach also limits the choices when it comes to purchasing SFPs (especially for 100G and above). A less expensive (but less accurate) option for multi-point services is to attach the SFP or NID on a separate port at the PE and inject probes into each service from there.

The “do-everything” is obviously the best approach for ensuring your service SLAs, but in reality, the cost of deploying and maintaining it can make it impractical. It can also end up being very redundant. In a multi-point service, the number of required probes is equal to the number of connections which, for a fully meshed network, is calculated according to the formula (n*(n-1))/2. Say you have a small Enterprise L3VPN service with 5 customer sites connected to 5 PEs. You’ll need (5 * 4 / 2) = 10 probes for each class of service in the L3VPN. If the customer paid for Gold, Silver and Best Effort QoS profiles, that’s 3 * 10 = 30 probes for one small service. Now imagine you have 500 L3VPNs on that same set of 5 devices. If you tested each service individually, then you’d be running 30 * 500 = 15000 probes, all probing the same 10 paths.

The Do Something Approach

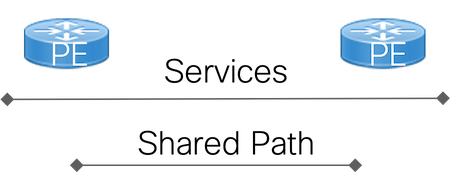

Given the scale and complexity issues, true per-service assurance may be unattainable. But there is a middle ground. Instead of taking a service as the unit of measurement, you could instead measure the shared transport paths and use that as a proxy for all the services that use those paths. Instead of 15000 probes for the 500 L3VPNS above, you could measure all 10 paths and 3 classes of service with 30 probes and use that in fulfillment of the SLA measurement.

Probing the transport path is not a direct measurement of the service performance: it measures the performance of a shared path that goes between the internally facing PE interfaces and may not capture service-specific forwarding issues inside the PEs themselves. But in many cases, it can serve as a reasonable proxy measurement since the majority of forwarding issues occur in the shared transport network. In addition, path measurement is a natural fit for the built-in probing capabilities of your routers, making it a relatively inexpensive thing to deploy.

Probing paths is inherently more scalable than probing services since many thousands of services might share the same path. However, relying on path probe data opens a new challenge: how to associate a service with a path (or paths). If all services use the shortest path between two PEs and the variations associated with ECMP paths can be ignored, then this might be “good enough.” In a more complicated scenario, a service might be configured to use a TE path but have fallen back to the shortest path because the TE path failed. Under these conditions, maintaining a real time mapping of services to paths represents a non-trivial amount of work for a management application (although, to be fair, the mapping of a service to the results of a service assurance probe requires work for external probes as well).

Conclusion

Although I’ve presented “nothing”, “everything” and “something” as separate deployment options, in reality, most providers will end up doing some of each.

In the end, there are no really hard and fast rules about “what to deploy, where” when it comes to service assurance. Design choices are always about trade-offs. Active assurance is important but often expensive. If a service is going to include premium SLAs that can only be measured by individual probes, then that expense can be included in the price of the premium service. Perhaps only a portion of the services offered by a provider actually need individually monitored SLAs. Prudent deployment of path measurement and best-effort design principles could suffice for the rest.

The good news is that service assurance is an area of active development for Cisco. New standards and tools are in process; new silicon will bring better scale and new features. IP networks may not have started with built-in assurance but the demands of today’s networks will continue to drive its evolution.

Leave a Comment