Inside IOS XR - Part 2

This is part two of the blog about the IOS XR’s software architecture. If you missed part 1, it’s advisable to start with it. In the first part, under the IOS XR Architecture Strategy, we covered the following concepts: Decoupled Planes Abstraction, State Management, Process Distribution Across Available Compute, and High Performance Messaging Infrastructure.

This second part covers the Data Distrubution and Access Design Patterns and High Availability & Upgradeability.

Data Distribution and Access Design Patterns

After scalable data partitioning, intelligent process placement to work with that data, and a high performance messaging infrastructure to enable communication among the processes working with this data, we now explore the next important aspect––the data distribution and access patterns that applications running in an XR system use.

Note that data distribution and access is inherently different from the messaging infrastructure/IPC mechanism––the messaging infrastructure provides a means of communication; it does not define the approach as to how to present data to other parts of the system that need the data, or how an application locates its resources that it needs for its operation. These issues are fundamental to the applications that run in IOS XR and are reflected in the implicit decisions an application is built upon.

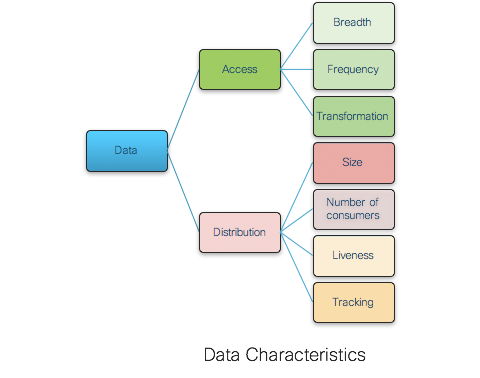

Understanding the inherent data characteristics of a router is essential in designing and optimizing the NOS properly. IOS XR is designed taking into account the data distribution and access patterns in a small single CPU IOS XR router to a large distributed router built from multiple chassis. Based on these insights, the IOS XR NOS data access and distribution characteristics can be pictorially categorized as follows:

The following informational section gives additional details about these characteristics.

Data Distribution and Access Characteristics

Data Distribution Characteristics

Data distribution has four sub characteristics: size of the data, number of consumers, liveness of producers/consumers, and tracking of producer.

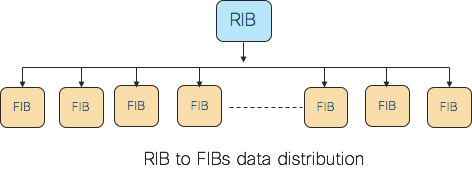

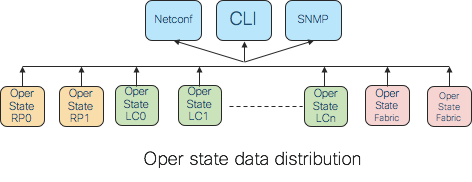

FIB routes is an example of a large amount of data that is going to be consumed by a large number of nodes in a distributed routing cluster. Operational data is an example of a large set of data that is going to be consumed by a few management agents. Throughput and latency are two performance metrics that matter in this kind of data distribution.

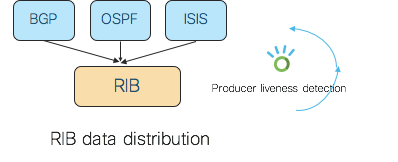

Many of the data sharing applications would want to know the state of producer(s); i.e. if the producer is active or has gone down so that they can take an appropriate action. Again, a good example of this is the interaction between a routing protocol and RIB. If a protocol has populated routes to RIB, the RIB should be notified when the protocol goes down so that it can stale the routes, and in the event that the protocol does not come back, it can delete those routes and promote backup routes, if any.

Many of the applications would also want to track producers of the data for various purposes. Going back to the RIB example, the routing protocols populating routes to RIB are the producers and RIB is the consumer. RIB explicitly tracks each such producer so that when all the producers are done with their routes, RIB declares routing convergence. This is an important state for the operation of the router.

In some cases, the data producer needs to be aware of individual consumers. In most cases, the producer needs to know only about the aggregate set of consumers, but in some cases, more intimate knowledge of the consumer is needed. For example, consider the case of RIB downloading routes to various FIBs across the routing cluster. Typically, this is done by putting all the consumers in a group and multicasting to them. If one consumer restarts, the producer should start a separate download session to that consumer so that it is aware of all the updates thus far while continuing to update the remaining consumers. The producer cannot suspend downloads to the other consumers because network events may happen at the same time and delaying downloads results in an unacceptable network convergence. Once the restarting consumer catches up with the rest of the group, the producer has to merge the consumer back with the larger multicast group.

Data Access Characteristics

On the data access front, if we look at breadth of data access, most data is accessed only by a few entities in the router cluster, and there is a very limited set of data that is accessed very broadly. One fine example for this is BGP’s private internal RIB structures. This data is referenced solely by BGP itself and the manageability agents. It is extremely large, and in many cases, is the majority of the data in the router cluster. BGP uses this data for computing routes and then injects specific paths into the RIB. Feature (ACL, QoS, etc.) data is another example of data with small breadth of access in terms of number clients. By contrast, there are other data items, such as the interface database, system configuration, etc., that are referenced by almost every other process in the router cluster.

Similarly, frequency of access of data items is highly variable, with a few data items that are very frequently accessed and the vast majority that are rarely accessed. For example, BGP provides an excellent example of a great deal of data that is accessed infrequently. Since BGP only makes incremental changes, once a path is in BGP’s internal RIB, and advertised to the RIB processes and any neighbors, that information may not be accessed again until the advertising BGP session fails. This could easily be days or weeks. On the high frequency side, the interface database can be accessed extremely frequently, such as every time an application needs to resolve an interface name into a data structure, access interface dependent statistics, or configuration. Thus, routing and configuration are a couple of examples of data that is accessed infrequently while statistics and interfaces are data that are accessed frequently.

For some data, the consumer consumes the data obtained from the producer as is. In some cases, consumers need to transform the received data.

Design Patterns

Based on the above examples, we can observe some usage patterns. There is small, frequently, and broadly accessed data and large, infrequently, and sparsely accessed data. There are large volumes of data that need to be moved to a lot of nodes, and there are small volumes of data that need to be moved to a lot of nodes.

For some of this data distribution, throughput or latency or both matter.

In some cases, once data moves to a location, it needs to stay there in a database for the subsequent accesses. In some cases, producer and consumer are completely decoupled, while in some other cases, they need to track each other. In some instances, data is consumed as is between producer and consumer, and in some other instances a data transformation is required.

What is the best way to satisfy these requirements? The IOS XR, after a careful consideration of data access metrics like the breadth of access, data size, frequency of access, degree of producer/consumer decoupling, liveness, data transformation requirements, is built around the following two fundamental data distribution/access patterns:

Data-centric

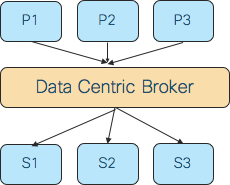

In a data-centric approach, IOS XR applications are structured around the data that is read or written. The identity of the processes that provide or consume the data is hidden in the infrastructure. Data is located by its description, and that acts as the rendezvous point for end applications. To that end, it mimics the publisher-subscriber model––more popularly known as “pub-sub”. Since processes that share data will not be connecting to each other to exchange data, this model is characterized by a looser coupling between processes exchanging data.

The time, space, and synchronization decoupling is achieved in IOS XR systems via a data centric broker between producers and consumers.

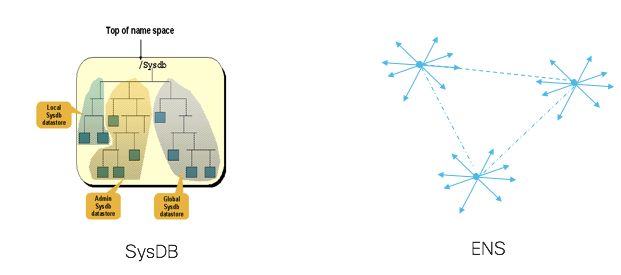

IOS XR designed the following two data-centric infrastructures based on the needs:

- SysDB - primarily a database with pub-sub messaging support.

- ENS (Event Notification System) - a data centric pub-sub messaging network.

The above categorization is very important to design a good NOS. For example, if we look at configuration data, it is essentially a state that is relatively small, fairly static, with a large set of consumers, and with almost no need of data transformation. Databases are great for storing such a state and to keep retrieving it. But when something changes in there, it is good to have “don’t call us, we will call you” support. Thus, SysDB provides messaging/notification support. SysDB, like Redis, is an advanced in-memory data structure server. Interestingly, like Redis, SysDB also acts separately as a publish/subscribe server.

ENS, on the other hand, is a decentralized flat topic based pub-sub messaging infrastructure that actually moves data from one place to another with reliability semantics. It is useful for the distribution of data that is written by one process to one or more processes on different nodes (a push model). ENS also works equally well in a pull model. Readers can come up and pull the data from the writer somewhere in the system. It is decentralized, as it is a collection of brokers spread across all nodes.

If we compare between ENS and SysDB, ENS creates direct links between distributed nodes, whereas SysDB is a logically centralized node which must be written to, then read from. In this respect, this is similar to the comparison between ZeroMQ and Redis, respectively. ZeroMQ/ENS is primarily a messaging infrastructure whereas Redis/SysDB is primarily a database. SysDB is covered in more detail in the following informational section.

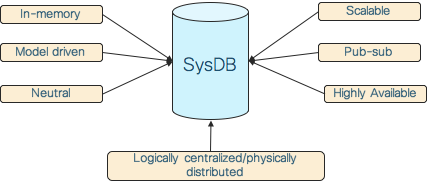

SysDB - Logically centralized, physically distributed, scalable, neutral, in-memory, highly available, model driven, pub-sub datastore

That is a mouthful of a description for SysDB, but each word in there is important, and collectively they define the concept and the power of SysDB. Configuration and operational data is a significant part of the router state, and the IOS XR’s SysDB is an advanced datastore to hold this data. SysDB has the following attributes shown in the picture, and each of these attributes is explained below:

- Logically centralized, physically distributed

The configuration and operational data is eventually consumed by various manageability agents interacting with the router on the northbound side. From an operations point of view, it is hugely important to present manageability agents the configuration/operational data in a centralized fashion, irrespective of the internal implementation. But internally the datastore should be distributed to achieve the required scalability, reliability, and responsiveness goals of large systems. IOS XR designed SysDB as a scalable distributed data store that presents a single logical view for the whole system’s configuration and operational data. Data is partitioned according to the principles mentioned elsewhere in this blog. Logically centralized/physically distributed is a concept that we see these days being used in many SDN Controllers as they try to present one logical global view of the network state while physically distributing the state across multiple nodes.

- Scalable

SysDB is scalable to a large number of nodes, large sets of configuration, high volume operational data, and to frequently changing operational data.

One can apply more than two million lines of configuration, and IOS XR works without a hiccup! One can retrieve large amounts of operational data from SysDB easily. This scalability can be attributed to proper data partition, and distribution of the required processing of the same, across the available compute.

Due to carefully designed shared state concurrency, many applications can also access the data in parallel, yielding greater scalability.

- Neutral

SysDB stores data in a format that is independent of the data formats of the manageability agents that it interacts with in the northbound direction and application backends it interacts with in the southbound direction. This is important for decoupling SysDB’s producers and consumers. All manageability agents work on the same data, and any new manageability agent support can be easily added.

With SysDB, applications do not have to track the data by its location, nor do they have to track the location of the data providers. Since the applications are unaware of the identity or location of data providers/consumers, they are unaffected if these parties crash or relocate.

- Model Driven

SysDB data is modeled and has evolved over the years to support native and Openconfig Yang models. For many years, XR has provided programmatic access to configuration and operational data.

- In-memory

The SysDB data is stored in memory (RAM). This is critical for the required performance.

- Pub-sub

SysDB is a hierarchical topic based publish-subscribe mechanism that decouples producers and consumers. It is designed to store fairly static data as well as dynamic, fast-changing, and/or high volume data. Subscribers are usually interested in particular events or event patterns, and not in all events.

- Highly Available

Active/standby HA is supported.

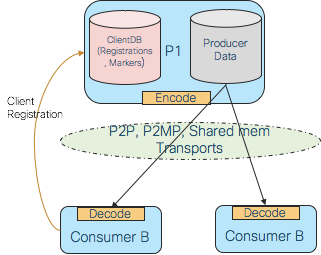

Process-centric

In the process-centric model, specific processes own the data, and any process interested in the data must contact the owning process to retrieve or update the data. Processes discover each other through a distributed directory services and register with each other for their interest on data.

One main benefit of the process-centric approach is the ability of the consumer to efficiently get liveness information about the producer. In cases where that liveness impacts the usability of the data, this is essential. This is not possible in a true data-centric system, as the producer is kept anonymously behind the publishing mechanism.

Since the producer of the data is aware of the data semantics, efficient data structures that are well-suited for the data being produced are used in IOS XR to build efficient notification mechanisms.

There are many use cases among router applications where a process-centric model turns out to be the best choice and IOS XR makes the optimal use of this construct.

High Availability Foundation

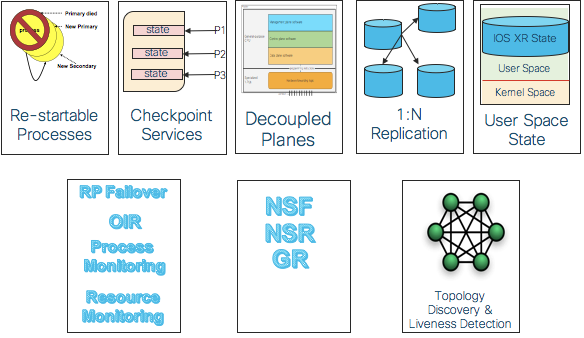

IOS XR is a modular system with separate and upgradeable components. Various software architecture constructs shown above lay a strong high availability foundation for IOS XR.

The fact that IOS XR services run outside of the kernel in separate address spaces means that the crash of an IOS XR process is isolated and does not crash the system, and in general does not crash other processes. Thus, a measure of fault isolation is available, and it can be exploited for purposes of service upgrade. Restartable processes are a major aspect of the high availability of an IOS XR system, and all IOS XR processes are required to be restartable.

Decoupled planes abstraction, explained earlier, also helps in the high availability of the system.

For restart and redundancy support, in general, checkpointing and replication services for local as well as remote checkpointing/replication are available so that restarted applications can start up warm or even hot. Replication services that allow checkpointing to more than one replica at a time are also available.

IOS XR also supports many levels of redundancy in the system, including switch-over of paired RPs, OIR scenarios and process-level, and role redundancy.

IOS XR has runtime monitoring of CPU and memory resources, so that applications that are using up too much of either of these system resources may be terminated or have their scheduling semantics modified to reduce their impact on the rest of that node.

IOS XR also supports NSF (Non-stop Forwarding), GR (Graceful Restart) protocols and NSR (Non-stop Routing).

The overall coordination of a router cluster, comprised of either single chassis or multiple chassis, requires that there be communications within the cluster, some sense of the topology of the cluster, and some consistent decision making capabilities within the cluster. To do this, the IOS XR has a top-level control protocol that is responsible for electing an overall leader of the cluster and computing the topology of the cluster.

Upgradeability Architecture

The modularity of IOS XR makes it possible to upgrade individual or smaller pieces of the software. That is, the same architectural features that accomplish fault isolation can also be exploited to achieve a finer-grain level of software upgradeability. The problem of software upgradeability starts at the smallest unit of software divisibility and goes to collections of these units. It is not at all a given with an IOS XR system that a software upgrade has much of an impact on the system. Much effort continually goes into reducing the impact of software upgrades, and it is the architecture of an IOS XR system, as well as the software organization, that enables this process.

Because much of an IOS XR process’s code may actually reside in shared libraries/DLLs, it is possible to replace/upgrade a portion of a process’s code by loading a new shared library. Because IOS XR processes are restartable, all that is required to pick up a new version of a DLL is to restart a process. Even some IOS XR processes do not restart, but simply unload and reload newer versions of DLLs.

The fundamental building block of IOS XR is the component. This is the minimum version-able unit of software. A component is potentially field replaceable. A component may contain a process’s executable file, DLLs for sharing code between processes, binary files for implementing a portion of the CLI, text files describing configuration rules, or other related data. A typical example of an IOS XR component is Border Gateway Protocol (BGP). The BGP is a component in the Cisco IOS XR system that includes the BGP process, the configuration and operational models, and associated processes.

IOS XR software is organized into packages at the highest level. Packages are collections of components and contain meta-data that indicates the compatibility of the components in the package with other components. Packages contain features that can be installed/activated/deactivated at runtime on an individual node, a set of nodes, or across the entire IOS XR system.

Conclusion

The blog started off by giving a brief introduction to IOS XR’s rapid evolution over the years. It then explained the architecture strategy via six steps: decoupled plane abstractions, state management, process distribution, high performance messaging infrastructure, data distribution/access patterns, and high availability and upgradeability. This logical sequencing, followed by details on each, hopefully gave you a better perspective of the IO XR design thought process.

I hope this blog gave good insights into various powerful architectural patterns built into IOS XR and how the IOS XR has pioneered various popular scalable and highly available frameworks in the context of a NOS. More importantly, it tries to give a sense of what it takes to build a carrier grade NOS and how much of a key role the infrastructure plays in a well designed NOS.

The IOS XR anticipated and baked in many architectural patterns that are considered trendy and cutting edge today, and the IOS XR evolution continues as networking scene keeps changing around it, as it has been over the last several years. IOS XR kept the foundations simple, which made complex things possible over the years. These solid foundations and continuous evolutions made IOS XR the best NOS for decades to come. For IOS XR, the change is a process and the future is the destination.

Leave a Comment