Service Assurance: A Guide For the Perplexed

Introduction

The concept of IP assurance is not quite as old as IP, but it's close: ARAPNET deployed IPv4 in January of 1983; by December, Mike Muuss had developed the ping utility to test reachability and delay. Techniques for assuring the network's forwarding functions through direct performance measurement have been evolving ever since, resulting in a confusing array of tools, protocols and choices. Many network architects are left wondering: "What should I deploy for assurance, where, and why?"

These are big questions, so I'm going to tackle them across a series of blog posts. This first one will cover the what and why of assurance. In part two, I'll cover the protocols and tools you have to work with. And in part three, I'll look at some key design questions.

What Is Service Assurance?

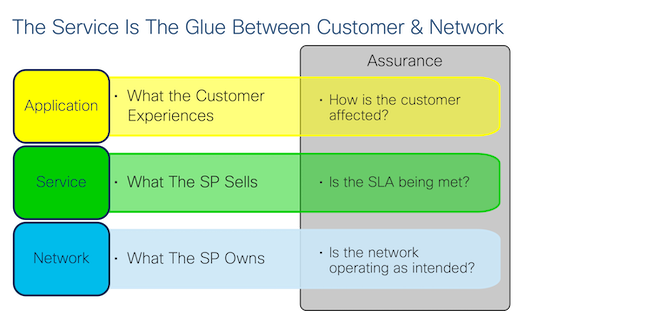

Assurance is the process of measuring performance and managing faults with the ultimate goal of optimization. You can "assure" many things -- a router, a path, a service, or an end-to-end digital experience. Assurance addresses different questions depending on the layer it applies to, so I like to divide it into three categories:

-

Network Assurance seeks to answer the question of whether the network devices are operating as designed: Are interfaces up? Are protocols running? Are CPU, memory and bandwidth utilizations within acceptable ranges?

-

Customer Assurance (also called Digital Experience Monitoring) includes Application Performance Monitoring. It measures things like page load times, voice & video quality and application responsiveness. This data could be provided by the application itself (e.g. WebEx metrics) or measured by a third party tool (e.g. ThousandEyes, AppDynamics).

-

Service Assurance sits between Network Assurance and Customer Assurance. A Service Provider is responsible for more than just making sure that routers are up and protocols are running (Network Assurance) but not usually responsible for the full Digital Experience (Customer Assurance) since the provider doesn't own all the applications, compute and other resources involved. The "service", then, defines the limits of the Service Provider's liability.

The Service Is The Product

As a network engineer, I am often guilty of thinking of "services" in terms of the technologies that enable them: L3VPN, L2VPN, EVPN, BGP, Segment-Routing, Traffic Engineering, etc. But if you take a step back, the only reason to invest in these cool technologies is because they deliver value to end customers. Those customers don’t buy EVPN or BGP; they buy point-to-point or multi-point services (along with enhancements like security and management) to meet specific business needs.

A service has a contract, a price, start and end dates, and a Service Level Agreement (SLA). The SLA defines the expected quality level of the service and can include metrics around availability, bandwidth, latency, loss and jitter.

SPs are highly motivated to assure that the service meets the SLA for several reasons:

-

Lost Revenue: If the SP cannot deliver the terms of the contract, then the end customer is entitled to a refund. In the case of outages and degradations, the SP must be able to prove that the failure did not occur in the SP network or else pay up.

-

Service Differentiation: SPs are always looking for ways to differentiate with new and improved services. Increasingly, monitoring and reporting are considered part of a differentiated service. One SP called this “Service Assurance as a Service” (SAaaS). For example, if you are providing a low latency service, you must be able to prove that the service meets delay guarantees. Service assurance is becoming monetizable.

-

Customer-driven Measurement: The end customer has the most immediate experience of the quality of the service. After all, it’s their data that’s traversing the service, and their applications that are directly impacted by service quality. Increasingly, Enterprises are investing in tools that can deliver very detailed metrics about the services they pay for. These tools include hardware-based probes from Netscout or Accedian, monitoring solutions like Thousand Eyes, or even the integrated tools in SD-WAN solutions like Viptela. These tools are often more accurate than anything the SP measures, leading to a situation where more than half of customer outages and degradation issues are reported by the end customers, not the SPs.

-

Customer Experience and Retention: One survey showed that 90- of customers only contact their SPs when they are ready to end their contracts due to service disruptions. Because service assurance data can give an objective measurement of customer experience, it can be used to understand and improve customer retention.

-

Reduced Customer Support Calls: One SP estimated that well over 50- of customer support calls concerned outages that did not involve the SP’s network or past outages that had been already fixed. By collecting service assurance data and providing it to their customers, SPs could offload those support calls to a self-service portal, conserving valuable technical support resources.

-

Streamline Troubleshooting: Swamped by barrage of network events and alarms, network operators are challenged to understand the root cause of reported service disruptions as well as the service impact of network faults. Good service assurance data can help localize failures and identify root causes more quickly.

Active Beats Passive for Service Assurance

A lot of Network Assurance relies on what are called "passive" metrics. Passive monitoring looks at state and statistics, such as interface statistics and memory utilization, on individual devices. Techniques like sFlow and Netflow are passive metrics, since they observe streams of traffic at different points in the network. Passive metrics offer a good picture of the health of a device at a given moment in time. Taken together, they create a good, high level picture of the overall functioning of the network.

While passive metrics are effective for Network Assurance, they provide only an indirect measurement of the health of a service. Everything can look good from a device perspective (BGP neighbors up, interface utilization normal, etc) but service traffic could still be getting delayed, dropped or sub-optimally forwarded along the path. The only way to know if the service actually meets the SLA is to measure traffic sent through the service’s data path. Since services like L2 and L3VPNs do not define an embedded assurance function, an additional mechanism must be employed to probe the data path of the service.

The most common way to do this is by injecting synthetic traffic to probe the network. This process is commonly referred to as "active monitoring." There are different kinds of probes that can be generated from different devices at different parts of the network, but all active monitoring involves sending, receiving and tracking traffic to directly measure the end customer’s experience of the service.

See RFC 7799 for more on the distinction between active and passive measurements as well as a definition of "hybrid" methods which modify customer traffic to carry performance data.

Conclusion

Unlike optical services (which carry performance, fault and path data in the header of every frame), IP/MPLS-based services like L2 and L3VPNs do not define an embedded assurance function. Nevertheless, end customers expect their SLAs to be delivered as promised. Assuring service performance through some form of active monitoring is increasingly a must-have for Service Providers.

In part two of this series, I'll take a deep dive into protocols and tools for active assurance.